This Advent we’ve chosen twelve different depictions of the Nativity, which we have discovered in the course of Blue Guides research trips around Italy—plus one final one from our latest title in preparation.

1. The ox and the ass and the baby in the manger from an early Christian sarcophagus (4th century) on display in Palazzo Massimo in Rome.

Related title: Pilgrim’s Rome

2. Mosaic of the Adoration of the Magi (5th/6th century) in the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna. The mosaics date from the reign of the Arian king Theodoric. Note the opulent dress and the Phrygian (eastern) caps of the Magi. The Madonna and Child are represented not in a stable but regally enthroned.

Related title: Blue Guide Emilia-Romagna

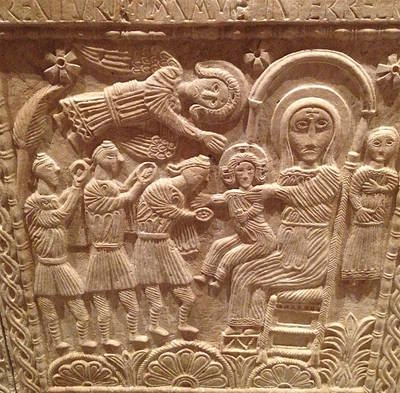

3. Sculpted relief of the Adoration of the Magi from the Lombard Altar of Ratchis (8th century) in the Museo Cristiano in Cividale. For a review of the current exhibition on the Lombards, running in Pavia, see here.

Related title: Blue Guide Friuli-Venezia Giulia

4. Mosaic of the Nativity, probably by Constantinopolitan craftsmen (12th century) from the cupola of La Martorana in Palermo. The bathing of the newborn infant is shown below right. Below left is Joseph, asleep and slightly apart from the others, as traditionally depicted in early renditions of this scene. Above him is a parallel scene of the Annunciation to the Shepherds.

Related title: Blue Guide Sicily

5. Fresco of the Nativity by an anonymous Lombard artist (14th century) in the Romanesque Basilica of Sant’Abbondio, Como. The washing of the infant is again shown as a separate scene, and once again, Joseph is withdrawn to one side. Note the friendly ass, licking the baby’s face.

Related title: Blue Guide Lombardy, Milan and the Lakes

6. Nativity scene from the predella of the famous Adoration of the Magi by Gentile da Fabriano (1423) in the Uffizi. Once again, Joseph is shown asleep, somewhat apart from the group. In a separate, parallel scene, the angel of the Lord appears to the shepherds in a brilliant glow from out of a sky spangled with lovely stars.

Related title: Blue Guide Florence

7. Fresco of the Nativity by Pinturicchio (late 15th century) in the church of Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome. The red brick and the breeze blocks of the dilapidated stable are particularly well done and Pinturicchio’s love of a detailed background is given full reign here: on the rugged hilltop ledge on the left are the shepherds keeping watch over their flocks. Below them the Magi are seen coming round the mountain at full tilt. And just behind the Madonna’s head is a delightful scene of a crowd crossing a bridge.

Related title: Blue Guide Rome

8. Detail of an early 17th-century terracotta tableau of the Nativity from the Sacro Monte of Orta San Giulio, Lago d’Orta. The scene seems identical to any other Nativity, but there is a twist: the infant here is not Jesus but St Francis of Assisi (and if you look carefully at the entire tableau, in situ, you will notice that it is not an ox and an ass that shares the stable with the Holy Family, but an ass and a mule). The idea that Christ’s life and the life of St Francis shared more than 40 parallels was dreamt up by a Franciscan Friar of the Counter-Reformation.

Related title: Blue Guide Piedmont

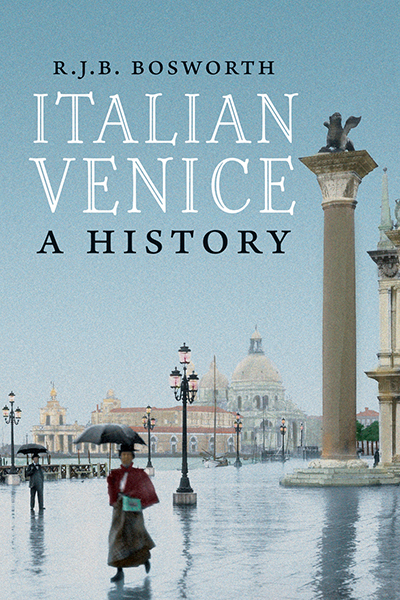

9. Altarpiece of the Adoration of the Magi by Federico Zuccari (1564) in the Grimani Chapel, San Francesco della Vigna, Venice. The altarpiece is badly damaged (the head of one of the Magi is missing) but the colours are beautiful.

Related title: Blue Guide Venice

10 and 11. Not paintings, frescoes or sculptures, but live installations. The first is from Manarola in the Cinque Terre, where every year from 8th December the hillside above the village is covered with hundreds of illuminated figures, creating a sort of electric crib scene. The second is from Genga in the Marche, where every year from Boxing Day until Epiphany, people form a living crib in the Frasassi Caves.

Related titles: Blue Guide Liguria and Blue Guide The Marche & San Marino

12. The Three Kings by József Koszta (1906–7). Koszta was a member of the plein-air artists’ colony known as the Nagybánya School. This work, which belongs to the Hungarian National Gallery, is a superb example of the colony’s style: the use of light and shade, of texture and colour, and involving the transposition of grand themes to a Hungarian peasant setting.

Related title: Blue Guide Budapest