Venice has been one of the world’s leading destinations for the cultural traveller since the 18th-century Grand Tour.

View the book’s contents, index and some sample pages, and buy securely from blueguides.com here »

Venice has been one of the world’s leading destinations for the cultural traveller since the 18th-century Grand Tour.

View the book’s contents, index and some sample pages, and buy securely from blueguides.com here »

Revoltella remained unmarried but he was not socially reclusive. His dinner parties attended by bejewelled beauties, his French chef’s extravagant concoctions and his gleaming gilded tableware were famous. At a gala banquet which he gave in honour of Franz Joseph’s brother Maximilian, on the eve of the latter’s departure for Mexico to take up his imperial appointment, the centrepiece, which drew gasps of wonder from the assembled guests, consisted of four hounds sculpted from butter attacking a wild boar confected out of sausage. It is difficult to gauge what motivated Revoltella. Was it business? Insecurity? A desire to impress? Ambition for social status, or for acceptance? A genuine regard for art? Did he have good taste? It is hard to say. His palace is a deliberate showpiece, but is neither impressively original nor depressingly vulgar. His chosen philosophers, whom he had sculpted at the top of the main stairs, were Galileo, Newton, Descartes and Leibniz: not thinkers, as such, concerned with the destiny of the soul, but physicists and mathematicians, an Italian, an Englishman, a Frenchman and a German. His collection of paintings contains the kind of thing that one might expect from a man of his time and status: Biedermeier portraits and romantic images of the Orient: there is a good Cairo street scene by Ippolito Caffi. In the study hangs a vivid Egyptian landscape showing the Suez canal slicing its way up from the Red Sea to Port Said.

From the library (which contains a copy of Revoltella’s own travel journal, which he wrote during his trip to Suez in 1861), a false door designed to imitate a bookshelf leads through to a small cabinet, once a bathroom, where some of the early treasures of the collection are housed, among them a model by Canova for his famous heroic nude statue of Napoleon holding a celestial ball intended to carry a Winged Victory. (The completed statue, in Carrara marble, never pleased the little emperor. He felt that the golden Victory figure appeared to be flying ominously away, and the statue was consigned to the vaults of the Louvre until purchased by Napoleon’s nemesis, the Duke of Wellington, who displayed it in his London home, Apsley House. It is still there.)

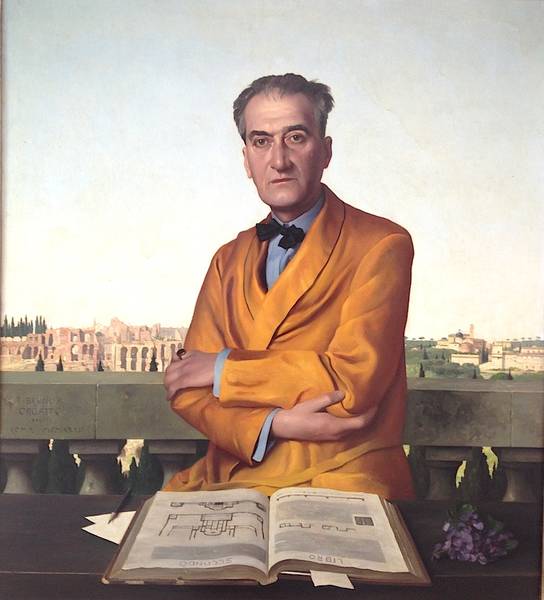

The collection in the adjoining building is rich in Italian art of the 20th century. De Chirico, Morandi, Carrà, Sironi, Burri: all are represented by at least one work. Particularly interesting are the local Trieste painters, whose work is less often seen in international collections. Piero Marussig is the best known; but also interesting are Carlo Sbisà (1889–1964), who found inspiration in the Italian Renaissance, and Bruno Croatto (1875–1948), known for his powerful realism.

Tucked away in a quiet nook in the sestiere of Castello is Palazzo Grimani, newly opened to the public, after years of restoration. I arrived late one afternoon, just as dusk was falling. As I climbed the wide stairway to the first floor, the sound of ethereal music floated down to greet me. A tall, slim woman in black was singing Josquin, accompanied on period instruments, to a small assembly in the portego. It was a magnificent way to begin a tour of this extraordinary place.

The palace was begun (so the Blue Guide tells us) around 1530 by Cardinal Domenico Grimani, son of Antonio (who was Doge from 1521–23), and work was continued to enlarge the palace by Antonio’s grandson Giovanni, Patriarch of Aquileia. It has been suggested that Jacopo Sansovino may have been involved in the work, collaborating directly with Giovanni Grimani.

Cardinal Domenico had a famous collection of Classical sculptures. At the death of his grandson Giovanni (in 1593) they were donated to the Republic, forming one of the first ever museums of Classical antiquities (and they are still on public view, constituting the main core of the Museo Archeologico in Piazza San Marco). Domenico was an important collector in other fields, too: he purchased works by Bosch, Memling and Dürer, drawings by Leonardo, and paintings by Raphael, Giorgione and Titian. At the death of the last descendant of the family in 1865, all the works of art which had remained in the palace were sold and dispersed. What you see today, as you visit the palace, are the rooms themselves, stupendously decorated in a wealth of original styles, the former backdrops for these marvellous works.

At one end of the portego, the central hall that runs the length of piano nobile, is the Cameron d’Oro where plaster casts of famous Classical sculptures (including the Laocoön) evoke the marbles once exhibited here by the Grimani. The room leading off it, the Sala a Fogliami, is perhaps the most remarkable in the whole palace, because of its ceiling, covered with a fresco showing thick foliage and fruit trees—peach, pomegranate, pear, medlar and quince—populated by birds which appear to be attacking each other. Amongst the plants the painter included maize and tobacco, recently arrived from north America. The motif of the birds, it is said, was designed to symbolise Giovanni Grimani’s stern stance against heresy, a reference to his acquittal by the Inquisition, who had accused him of unorthodox attittudes to predestination. There is a bench in the room: the best thing you can do is prostrate yourself on it, flat on your back, and just look:

The extraordinary Tribuna was designed by Giovanni Grimani to display some 130 pieces of his statuary collection. Its sober atmosphere recalls the vestibule of the Laurentian Library in Florence—and it is now empty except for the Ganymede (a Roman copy of a Hellenistic original) which has been returned from the Museo Archeologico and now again hangs from the centre of the ceiling as it did in the Grimani’s day.

The Sala di Doge Antonio, and the little vestibule and chapel adjoining, are decorated with exotic marbles. The ceiling of the chapel is decorated with the following Latin motto: “Thou has protected me, O Lord, in thy tabernacle, from the slander of tongues.” By fireplace in the main room is a bronze bust of the Doge himself, a stern-looking man. Leading off from here are the Camerina di Apollo and Camerina di Callisto, decorated in the 1530s in stuccowork and fresco.

In an adjoining room are four extraordinary panels by Bosch (c. 1503) representing Paradise and Hell, the Fall of the Damned, and the Ascension to Heaven. The image of the Fall is memorable in the extreme: like a scene from a nightmare, souls are represented as having tumbled through a great hole, and they now sit helpless in the dark, far from the light which streams through upon them, unreachable, from the manhole high above their heads.

Adapted by Annabel Barber from the forthcoming new edition of Alta Macadam’s Blue Guide Venice.

As work on the new edition of Blue Guide Venice gets underway, and as I start planning my next trip there, my thoughts turn to the island of Burano. On a sunny day in February—and if we’re lucky there will be some sunny days this month—the colours of Burano’s houses are at their absolute best.

Burano is most famous perhaps for three things: its lace, its S-shaped biscuits, and its colourful façades. But there is more. The little church of San Martino, for example, approached down the wide Via Galuppi, contains a wonderful painting by Tiepolo. It is a rare treat to be able to admire a work of Tiepolo without having to crick your neck back to look at a ceiling fresco. This is a Crucifixion, commissioned by a pharmacist in 1722 (his donor’s portrait is included, in an oval frame at the far left, not shown in the detail here). Christ is depicted victorious, his eyes cast upwards. One of the thieves has already being taken down and his body is being untied; the other still writhes upon his cross. In the foreground, the grieving, grey-faced Virgin swoons into the arms of the two Marys.

Via Galuppi and Piazza Galuppi, where the church stands, are named after the island’s most famous son, the composer Baldassare Galuppi, who was born here in 1706. He was immortalised by Browning, in “A Toccata of Galuppi’s”.

“Oh Galuppi, Baldassaro, this is very sad to find!

I can hardly misconceive you; it would prove me deaf and blind;

But although I take your meaning, ’tis with such a heavy mind!

Here you come with your old music, and here’s all the good it brings.

What, they lived once thus at Venice where the merchants were the kings,

Where Saint Mark’s is, where the Doges used to wed the sea with rings?

Ay, because the sea’s the street there; and ’tis arched by—what you call

—Shylock’s bridge with houses on it, where they kept the carnival…”

The skipping rhythm of the verses is intended to imitate the notes of a toccata played on a clavichord. The themes of gaiety and masked revelry and death are particularly relevant in a Venetian February, the season of Carnival and Lent. Though if the sun shines, there is no need to dwell on them for long.

There are plenty of places to eat on Burano. Al Gatto Nero offers local fish dishes, including a risotto di gù alla buranella (Burano-style goby risotto).

by Charles Freeman

At the end of a recent tour of Friuli in October, I asked members of my group what they had enjoyed most, High on the list were the Tiepolos in the Patriarchal Palace in Udine. Commissioned in the 1720s by the Patriarch of Aquileia, Dionisio Dolfin, member of an aristocratic Venetian family, they were designed to highlight the link between the Patriarch and the patriarchs of old, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. Perhaps the two finest works are Rachel hiding the idols from her father, Laban, and The Judgement of Solomon. Their state of preservation is remarkable.

Tiepolo was still young, just thirty, when he began his commission, but already his work is assured. The colours are rich, the soaring perspectives painted with the confidence that was to stay with him throughout his Europe-wide career. He always comes across to me as someone who loved painting for its own sake, not as a means of sorting out some internal angst.

So it was frustrating to arrive at our next destination, the vast Villa Manin, and to find that we were a few weeks too early to see the majestic Tiepolo exhibition that opened there on 15 December (and lasts until 7 April). It is open every day, even on the afternoon of Christmas day (further information and booking on the Villa Manin website).

The exhibition boasts a wide scope. There are works from Venice and the villas of the Venetian countryside, where Tiepolo spent much of his life, many of which have been brought back from the galleries as far flung as new York, Montreal, Helsinki and Stockholm. Several of the canvases are enormous—luckily the central rooms of the Villa Manin can take them—together with the preparatory drawings for them. So the vast canvas (7m by 4m) of St Thecla freeing the city of Este from the plague, from Este cathedral (completed in 1759 in commemoration of a plague of 1638) is there together with the preparatory study now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York. The opportunity has been taken to restore the canvas: in fact there is a sense of opulent generosity about this exhibition that is far removed from the austerity that is afflicting so many Italian archaeological sites at the moment.

The exhibition is linked to the Patriarchal Palace in Udine and the Sartorio Museum in Trieste, which contains a fine cache of Tiepolo drawings. So the show promises a true feast for those who find themselves drawn to an artist who is perhaps the finest Italian painter of the 18th century.

Udine and Friuli are covered in Blue Guide Northern Italy and Blue Guide Concise Italy. Charles Freeman is historical consultant to the Blue Guides and author of Sites of Antiquity: 50 Sites that Explain the Classical World.