We came to Sabbioneta the small Renaissance city brought to its final form by Vespasiano Gonzaga in 1590, in the spring of 2015 to check it as a possible stop on a tour. Despite its World Heritage status, Sabbioneta is still little visited; we were almost alone as we explored its buildings and walked around its walls. Yet it is fascinating in itself as a time capsule of late 16th-century architecture, above all in the exquisite theatre, just a few years later than Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza but echoing it in style. It came as no surprise to find that it is the work of Vincenzo Scamozzi, who had finished Palladio’s masterpiece after his death.

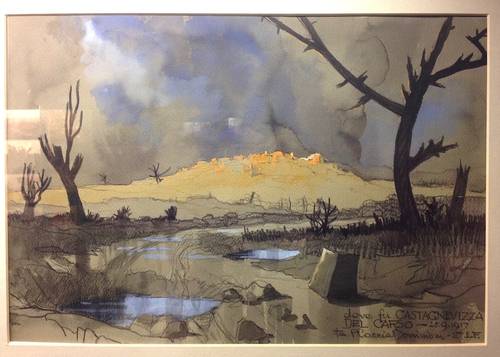

The architect James Madge, who died in 2006, first visited Sabbioneta in January 1988, a day on which the fog of the Lombardy plain enveloped the city. As he walked around, buildings loomed from the mist and then disappeared, perspectives came and went, the length of the Galleria Grande seemed to merge into nothingness. It gave him the sense that there was more to Gonzaga’s creation than simply ‘the ideal city’ and he became fascinated by Vespasiano Gonzaga himself, ‘for whom architecture was a means to externalise a complex, often contradictory and passionate nature’. Why was Vespasiano so determined to create this small (probably no more than 2,000 citizens), idealised city in a comparatively remote spot on the banks of the Po?

The result of Madge’s researches are Sabbioneta, Cryptic City, published by Biblioteque McLean (London, 2011). Madge begins by tracing Vespasiano’s background. His father had died when Vespasiano was only eleven months old, leaving the township of Sabbioneta as part of his inheritance. This was only a cadet branch of the family. Vespasiano was never to enjoy the wealth of his cousin Guglielmo, the head of the Gonzaga family in Mantua, with his thousand dependents and twenty residences, but his mother was from the ancient Colonna family and Vespasiano was profoundly conscious of his status as one of noble heritage and status. He was lucky to be brought up in the household of his aunt Giulia Gonzaga, a childless window of great learning who ensured he had the best education in the classics.

He was then sent off to the court of his uncle, Philip II of Spain. Perhaps it was because as an Italian he would always be an outsider, perhaps the hothouse aristocratic atmosphere of Philip’s court would have stifled anyone who was not exceptional, but Vespasiano’s achievements in Spain were always modest. There were some reckless charges in battle which he was lucky to survive, and he proved a capable diplomat, but lacked the éclat or presence to go further. His most senior posting, as Viceroy of Navarre, appears to have been largely honorary.

There were also problems in his intimate relationships. His first marriage proved childless and he was alienated from his wife: there were rumours of her infidelities. His second marriage, to the Spanish Anna of Aragon, did produce a daughter, Isabella, and a son, Luigi, but Anna appears to have suffered from deep depression and had withdrawn from Vespasiano’s life years before her death. Now came the tragedy of his life. Luigi, always sickly, died while still a boy, a terrible blow for a father who was so conscious of his noble heritage. A third marriage, conceived in desperation in the last hope of providing an heir, was childless. The Gonzaga-Colonna line was due for extinction. Madge analyses the poems that Vespasiano left. They were hardly of great quality but show him as solitary and unfulfilled, the women he addresses hopelessly idealised.

So this perhaps helps explain the impetus for a semi-private world of his own creation, a place where Vespasiano could act out the role of cultured humanist. Sabbioneta was a lifelong project, with its founder escaping when he could from his duties in Spain. He began in 1556 by creating a community from the existing township that he had inherited. Citizens would lose their privileges if they did not reside there, absentee clergy were summoned back to their parishes, a monastery was relocated within the walls and no local market was to be held outside the central piazza. Madge notes how the inhabitants soon took pride in the new town that was rising around them and their loyalty was reinforced by the benevolent rule of their patron. Vespasiano’s tolerance extended to a community of Jews, rare at a time when the Counter-Reformation was gathering strength (one can still visit the city’s synagogue). Though he kept his religious beliefs to himself, his range of contacts showed he was never closed to religious diversity.

This is not a guidebook to Sabbioneta, although Madge uses his architectural experience to trace some of the influences from the treatises of Leon Battista Alberti (whose masterpiece of Sant’Andrea in Mantua is not far away) and, through Alberti, back to the Roman architect Vitruvius. Vespasiano was steeped in the Roman world. He had himself presented as a Roman in the fine bronze statue of him by Leone Leoni (1588), originally outside the ducal palace but now crowning his tomb in the church of the Incoronata. Rome, as Madge puts it, ‘is immanent as a felt presence at Sabbioneta’. The city is aligned on an axis that leads southwards to the city, there are frescoes in the theatre of Rome as it was in Vespasiano’s day and his own seat there is placed in front of a fresco of his namesake, the emperor Vespasian.

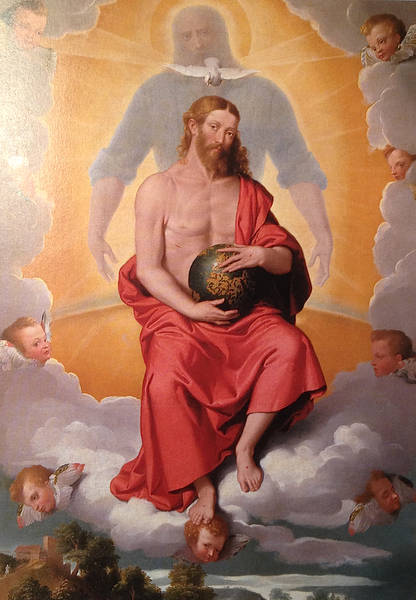

Unlike Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico, the theatre in Sabbioneta is conceived as an independent building, probably the first of its kind. With its statues of the Olympian gods, frescoes of the emperors and of Rome, and a painted loggia of local figures (reminiscent of the Veronese’s frescoes from the Villa Barbaro), it is a wonderful place to visit. Nearby the Palazzo Ducale (Vespasiano was created Duke of Sabbioneta by the emperor Rudolf II in 1577) has much of interest, but perhaps one comes closest to Vespasiano himself in the private apartments of the Palazzo del Giardino. The frescoes here, by Bernardino Campi, show his fascination with Roman literature: there are scenes from the Aeneid and mythology from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Madge attempts to make connections between the preoccupations of Vespasiano and the subjects of the frescoes but it could equally be said that these are typical expressions of the 16th-century humanism. What is special is the Galleria Grande, 96m long. Originally Vespasiano’s collection of antique statues were spaced along the walls, but towards the end of his life, he took out the busts of famous commanders and refilled their niches with antlers and other ‘natural’ objects that he had acquired while visiting his patron, the emperor Rudolf in Prague. It shows that, even in his last years, Vespasiano was still intellectually inquisitive.

The theatre was inaugurated in February 1590 during carnival celebrations and a troupe of comedy players was based there over the following months. However, Vespasiano was ailing and he died in 1591, leaving the city to his daughter and her husband. Over the years that followed the city stagnated. The statues went to Mantua in the 18th century. The theatre passed from granary to warehouse, from barracks to the local cinema, before its restoration in the 1950s.

Meticulous readers will note that James Madge died in 2006 and Sabbionetawas not published until 2011. It is good that the book was rescued for publication, although the material, particularly that on Vespasiano’s life, might have been reorganised in a better chronological sequence. In his attempt to find the roots of Vespasiano’s personality, Freud is brought in to help, but it is hard to isolate Vespasiano’s inner traumas from the wider world in which he lived. In so many ways he represented the cultural elite of his day: tolerant, well-read, half-lost in the Classical world. Where this book has wider appeal lies in the generous selection of 16th-century humanist texts that Madge has brought together. Sadly the illustrations at the end are rather cramped but overall Madge does well to give an interpretation of Sabbioneta that explains why it came to be.

Reviewed by Charles Freeman, historical consultant to the Blue Guides.