In the eastern corner of the City of London, close to the old walls and to the place where the Aldgate once stood, is a small church, that of St Olave Hart Street. It is dedicated to King Olaf II of Norway, who fought with King Ethelred against the Danes at the Battle of London Bridge in 1014. He was canonised in 1031, so the church in London must have received its dedication after that date. In 1666 the Great Fire came within 100m of St Olave’s before the wind fortuitously changed direction, thereby saving it from being engulfed in flames. (The church was not so lucky during World War Two and sustained two direct hits during bombing raids; it has been lovingly restored and King Haakon VII of Norway laid a stone from Trondheim Cathedral, the burial place of St Olaf, in the sanctuary.)

The church is famed as the burial place of Samuel Pepys; and high up on the north chancel wall, left of the altar, is a bust of Pepys’ wife, Elizabeth (d. 1669). To the right of the altar is a wall tablet commemorating William Turner (d. 1568), Dean of Wells, militant Protestant and father of English botany. Close by, left of the southeast window, is a painted alabaster portrait bust of Turner’s son, Peter, ‘Doctor in Physick’, who attended Sir Walter Raleigh in the Tower. In 1603 Peter Turner wrote a treatise in support of plague cakes: little phials of arsenic to wear around the neck or in the armpits in order to ward off infection. Turner was a keen follower of Paracelsus, the great German physician known for his advocacy of the use of poisons to control disease: he was both early homeopath and pioneer chemotherapist. He recommended the use of mercury to combat syphilis, for example. Efficacious to a degree, but of course toxic if used in too great quantities. Paracelsus also used a solution of lead as a treatment for goitre. Peter Turner may have been right to champion the use of these poisonous pomanders. The full title of his treatise is important: ‘The opinion of Peter Turner Doct. in physicke, concerning amulets or plague cakes whereof perhaps some holde too much, and some too little’. Dosage is all. In 1605, Francis Bacon published his Advancement of Learning, in which he also mentions the use of plague cakes: ‘It hath been anciently received, for Pericles the Athenian used it, and it is yet in use, to wear little bladders of quicksilver, or tablets of arsenic, as preservatives against the plague: not for any comfort they yield to the spirits, but for that being poisons themselves, they draw the venom to them from the spirits.’

Turner’s bust (c. 1614) disappeared from St Olave’s during the confusion of the Blitz but—in another of the strokes of luck that seem to attend this church—it resurfaced in 2010 at public auction. In 2013 it was reinstalled after a 70-year absence, in a partial recreation of the original monument.

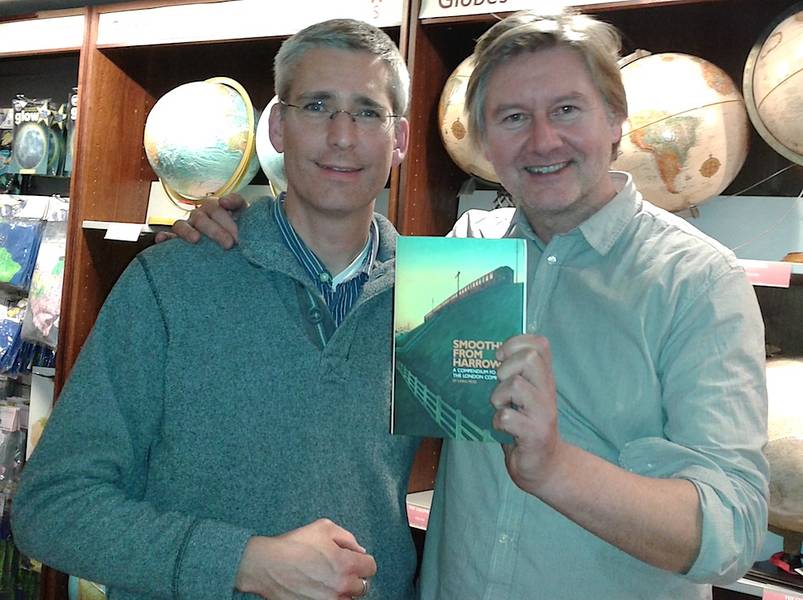

For St Olave Hart Street, plague cakes and much more besided, get Blue Guide London (18th edition), compiled, written and updated by Emily Barber.