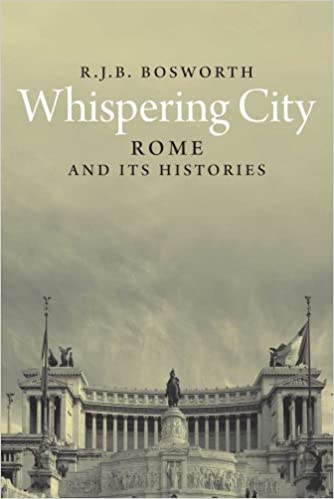

I first arrived in Rome in January 1966 when I was eighteen. I had had a long journey by train from London but I have never forgotten the emotional impact as my taxi sped by the Forum. All the hours I had spent trying to construe the speeches of Cicero and the odes of Horace gained meaning and since then I have never been able completely to separate ancient texts from the places they were created.

I still know of no other city where the histories and myths intermingle quite so powerfully as they do in Rome, for any period of its past one chooses. Even the traditional founders of the city, Romulus and Remus, were heirs to the myth of Aeneas. What Bosworth achieves in this sophisticated and penetrating history is to show how the Roman pasts have pervaded the political and religious life of the city since 1800. The revolutionary French, the austere and embittered popes, the leaders of the new secular government after 1870, Mussolini with his bombast of a rediscovered empire, none of these could never escape from or fail to manipulate some precedent. Every leader sought to find the ‘right’ Roman past—republican, imperial, Christian or nationalist—to use for political resonance whatever the cost. Mussolini blindly destroyed large parts of medieval Rome to claw out the imperial ruins that lay buried beneath it.

What I loved about this book was Bosworth’s acute sensitivity to every nuance of Rome’s past. Symbols were refashioned to meet each contemporary need, however transient it might prove. I warmed to the story of how, during the ‘revolution’ of 1848–49, the cross on St Peter’s was, in the absence of the fugitive pope, painted in republican colours, while in the 1948 elections, the Italian communists linked Giuseppe (Joseph) Garibaldi, to another Josef, Stalin. (The Church responded with ‘At the urn, God sees you but Stalin does not’.) And I never knew that the last surviving ship of the papal navy was a paddle-boat called the Immaculate Conception.

The perpetual game-playing between popes, outraged at the loss of their patrimony in 1870, and city rulers achieved high levels of drama. When in 1889 the Roman government launched a grand unveiling of the statue of Giordano Bruno, burned by the Inquisition in 1600, Pope Leo XIII retaliated by spending the day prostrate before a statue of St Peter. When the Fascists commemorated the anniversary of the March on Rome on 28th October, Pope Pius XI countered with the institution of a new feast day, of Christ the King, for the last Sunday of October. In the great public ceremonies, blackshirts offered no competition to a pope clothed, as Pius was on one occasion, ‘in a huge silver mantle interwoven with gold’. Whatever Il Duce’s ambitions, no one knelt when Mussolini passed by. They did in their thousands when the pope did. Well might Pius XII reassert Rome’s primacy as the universal Christian centre of civilisation when the Fascist regime collapsed ignominiously in 1943. One of his successes was to secure the placing of figleaves on the virile genitalia of Fascist heroic statuary during the Holy Year of 1950.

Assiduously researched and always absorbing, this book should have an appeal far beyond lovers of Rome. Anyone sensitive to history is aware of how easily the past becomes mythical and /or fugitive. Sniff the air in Rome and, above the traffic fumes, you can sense the currents of nostalgia merging, separating, remingling, swirling around the ruins of past and present. Bosworth shows how even the most determined rewriters of history, Mussolini prominent among them, were out-manoeuvred by the insistent presence of alternative myths which subverted their proclamations of the revival of an ‘eternal city’. Rome is indeed ‘eternal’ but primarily, perhaps, in its ability to eternally manipulate its past.

Reviewed by Charles Freeman, historical consultant to the Blue Guides and author of Sites of Antiquity: 50 Sites that Explain the Classical World. His Holy Bones Holy Dust, a study of the medieval cult of relics, is reviewed here.