The famous Savoy collection of Egyptian antiquities was largely gathered during the 18th and 19th centuries and was extensive enough by the 1830s for Champollion to do much of his work on deciphering hieroglyphics in Turin. For years the collections seem to have gathered dust but there has now been a vibrant revival of the museum. Somehow it has caught the imagination of the city. It buzzes with energy and school groups, with the number of visitors now topping half a million a year. At first I was a little disappointed with the traditional cases of artefacts in the first rooms but the sculpture gallery is stunning, and one has to accept that this is a better collection than that in the British Museum. There are especially good arrangements of everyday life found in undisturbed tombs.

The finest restorations are to be found in the coronet of palaces and hunting lodges that encircles the city: the “Corona di Delizie” or “Crown of Delights” as they have been known since the 18th century. The Villa della Regina is walkable from the centre, along the Via Po, through the majestic Piazza Vittoria Veneto, across the Po and up the hill past the Neoclassical church of the Gran Madre di Dio, built to celebrate the return of King Vittorio Emanuele I after the Napoleonic hiatus when Piedmont had been ruled from France. The villa originally dates to the early 17th century but derives its name from Queen Anne-Marie, the niece of Louis XIV who married Vittorio Amedeo II of Savoy, and made it her home. She died here in 1728. There is an elegant ‘classical’ garden behind the villa and its private vineyard is still kept up.

Forty minutes from the centre of town is the Venaria Reale, the vast 17th–18th-century hunting lodge of the royal family. Virtually abandoned after the third wife of Carlo Emanuele III died here in childbirth in 1741, it has now been subject to a massive restoration programme. The first rooms of the Reggia, the main palace, are devoted to the Savoy dynasty, which originated in Savoy in 1003, so making it the oldest in Europe. (With the dynasty secure in Piedmont, Sardinia and then Italy, Savoy itself was passed to France in thanks for French help in the unification of Italy in 1860.) Here you can find the dynasty’s members listed and thus sort out the rulers and their marriages into the other royal families of Europe. A gallery of (reproduced) portraits of all the more significant members provides further help. The next rooms show the growth of Turin as a capital and document the works of the two great architects of the dynasty, Guarino Guarini in the 17th century and Filippo Juvarra in the early 18th.

Juvarra (1678–1736), who arrived in Turin in 1714, was appointed architect of the Venaria Reale and completed the astonishing vestibule there as well as the palace church dedicated to St Hubert, the patron saint of hunting. Yet this is only one part of the complex that can be visited. There are two exhibition areas (with exhibitions of the fashion designer Roberto Capucci and Lorenzo Lotto on show until the summer of 2013), the royal Savoy barge as well as many of the original rooms of the earlier palace. Then there are the gardens now being recreated after falling into decline in the 19th century. There is a complicated ticket system under which you pick and choose what you want to see, but we found that it is better to go for the €20 ticket that covers everything. The planned 18th-century town, the borgo antico, alongside the palace, is full of eating places.

When the royal family abandoned the Venaria Reale, it was Juvarra who was asked the design the new hunting lodge at Stupinigi, to the south of the city. This is a wonderful building and the restoration is magnificent. The lodge is owned by the order of St Maurice and its future was in doubt when the order fell into financial problems but on 15th March, 2013, it opened again and it is hoped that this will be permanent. Every room is beautifully decorated, not least with 18th-century hunting scenes set in the adjoining park. The central hall is simply staggering: Juvarra’s architecture, if you do not know it, is altogether a revelation, whether here at Stupinigi or in the entrance hall he designed for the Palazzo Madama back in the city or at the Superga, the ‘victory’ church on a hill overlooking the city that later became the mausoleum of the royal family.

After the Second World War, the royal family, discredited through their association with fascism, went into exile and many of their former palaces, especially those in Piedmont, began to crumble. The rejuvenation of these buildings has been astonishing and puts Turin back on the map as one of the finest cities in Europe for the Baroque.

There are many other sights in Piedmont to explore. The Castello di Masino, beautifully restored by FAI, the Italian ‘National Trust’, was our favourite but we also loved the castle at Issogne, on the old Roman road to Gaul, across the regional border in Valle d’Aosta. All these delights will be crammed into my forthcoming tour of Turin and the surrounding area in May.

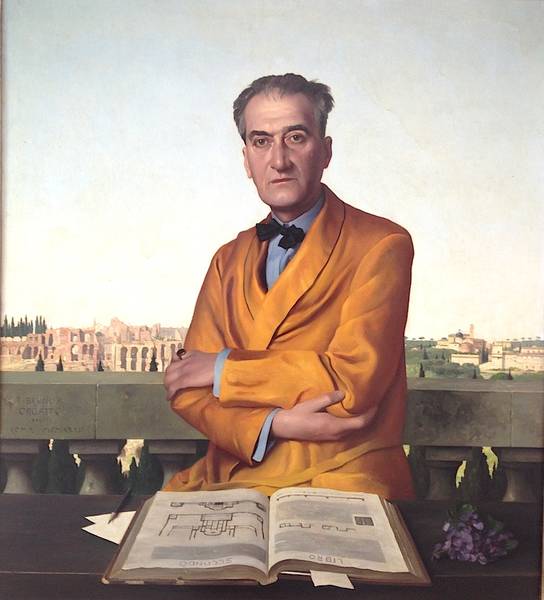

Charles Freeman is historical consultant to the Blue Guides and author of Sites of Antiquity: 50 Sites that Explain the Classical World.