“Anna: Fictitious Female Fates” (Anna: Változatok székely asszonysorsra) is the title of a disarmingly thought-provoking exhibition at the Hungarian National Museum, on tour from the Rezső Haáz Museum in Székelyudvarhely (Odorheiu Secuiesc, Romania). It follows the fortunes of the imaginary Anna, a Hungarian-speaking Székely, born in east Transylvania in 1920, the year that Transylvania was awarded to Romania in the dismemberment of Austria-Hungary.

To participate in the exhibition (you can’t just view it; it is fully audio-visual), you need to download the sound files via an app. The show is divided into numbered viewing/listening stations, each with its own little set, each representing a stage in Anna’s life. You follow her around, listening as she tells her story.

Her childhood is much like that of any other rural Székely girl. Tough but not deprived. She gets a few years of schooling before putting her shoulder to the family wheel, tending crops and looking after the animals. In due course, the expectation is that she will marry.

And so she no doubt would have done, had it not been for the handsome boy at the village barn dance…

So far, it’s a Victorian novel. But Romania in 1920 was a long way from that world. These were years of turmoil and dislocation—and yet despite the disruption (or because of it), Anna arguably ended up with more opportunities than she would have done had her world not fallen apart. It’s difficult to review the show without including an enormous spoiler. Suffice to say that the boy at the dance is (of course) a rotter. Anna finds herself pregnant, ostracised and potentially ruined.

Then comes the bifurcation of the ways that makes this exhibition work. Anna, the undone village girl (and you, the visitor) are presented with two alternatives. Do you opt for (A): an abortion at the filthy hands of ‘Aunt Rebecca’, flight to the big city (Kolozsvár/Cluj) and a job as maid of all work in a wealthy Jewish household? Or do you take (B): the crippled, war-wounded older man your father finds for you, who needs a nurse and in return is prepared to adopt your child? (If I had to quarrel with any aspect of the exhibition, it would be this. Can we really believe in this middle-aged miracle of mercy, prepared to take soiled goods? It seems to be the one slightly false note.) In any case, you turn left into the “farmhouse living room” for option B and right to the “railway station” for option A—and in the end (don’t read this if you don’t want to know), it doesn’t matter which path you choose, because both will lead to the same urban tower block, where you will spend your declining years fed and warm but on your own and lonely, listening to the TV (when there’s electricity, this is ’80s Romania) to blot out the silence.

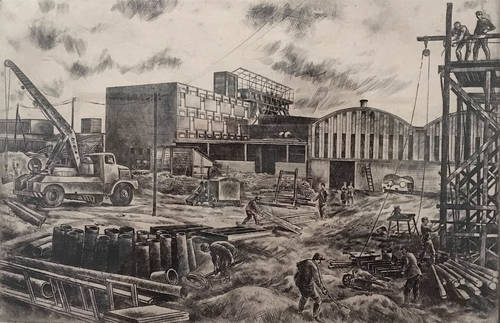

In the meantime you will have run the gauntlet of the Holocaust, Communism, collectivisation, industrialisation, defection to the West and the impending execution of Ceaușescu. And you will ask yourself: Do I have regrets? (Yes and no.) Would I start my life all over again if I could? (Absolutely. Hope always triumphs over experience.)

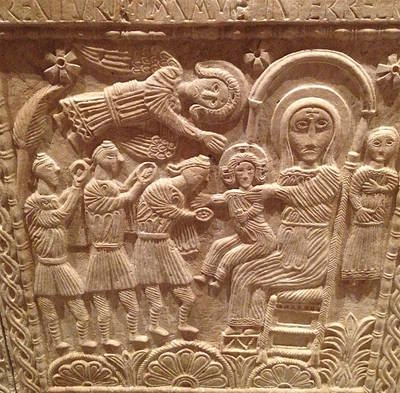

The whole exhibition is a subtly understated Gesamtkunstwerk. At first, you wonder if it’s going to be a bit amateurish. But you soon get sucked in and begin to notice that careful applied-arts and ethnographical research has gone into the choice of furnishings for each “set”. The items are not labelled; they speak for themselves. This is an exhibition which manages to impart its content without a single wall text. The historical events and background aren’t explained either. They are just the cards that Anna is dealt, the ingredients for the whole construct, and therefore you the listener are forced to try and make sense of them.

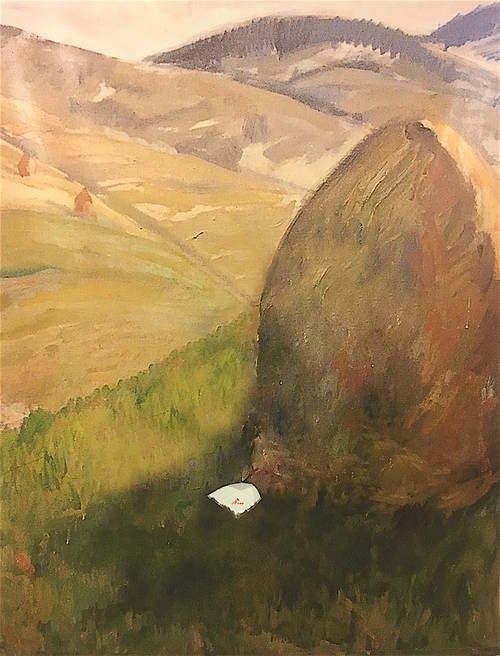

Appearing like a leitmotif at every stage of Anna’s passage is a bright white handkerchief embroidered with her name. She drops it at the foot of a haystack during the rough-and-tumble of that fateful barn-dance encounter. It’s a dainty thing, an item which, in the normal run of events, might have been expected to form part of her trousseau. One does have to wonder though, considering the political havoc that was to ensue, as Austria-Hungary was torn to shreds and stitched back together in a zany new patchwork, the social order turned completely on its head: would Anna’s life really have been better if she had held on to her maidenhead and married the boy next door? The answer isn’t obvious—which is what makes this show so successful. The cluster bomb which 20th-century history detonated upon society and its established institutions brought misery, it’s true. But opportunities as well.

Ultimately, “Anna” asks one of the most fundamental of all human questions. Can flouting the rules lead to greater happiness than obeying them? Our desire for self-determination, our rejection of socio-religious moral codes and our demand to inhabit a stable world and yet not to bow to all its laws, have led us to lonely isolation in urban tenements. But which is better? Loneliness on one’s own terms or the support mechanism of suffocating togetherness in a tiny village community, where if you overstep the mark, you’re out?

Thus doth the Great Foresightless mechanize

In blank entrancement now as evermore

Its ceaseless artistries in Circumstance

Of curious stuff and braid, as just forthshown.

Yet but one flimsy riband of Its web

Have we here watched in weaving…

The ‘Spirit of the Years’ speaks these lines at the conclusion of Thomas Hardy’s The Dynasts. Anna and her handkerchief might be a ‘flimsy riband’. But they are also part of the ceaseless artistry of circumstance.

Reviewed by Annabel Barber.

“Anna: Fictitious Female Fates” (Anna: Változatok székely asszonysorsra), runs until the end of April at the Hungarian National Museum in Budapest. For more on the Rezső Haáz Museum and the Székely area of Transylvania, see Blue Guide Transylvania: The Greater Târnava Valley.