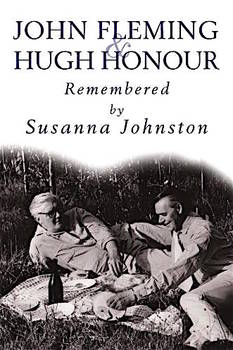

Susanna Johnston, John Fleming and Hugh Honour Remembered. Gibson Square, London, 2017.

John Fleming and Hugh Honour’s A World History of Art (1982 and later editions, the 7th as recently as 2009) was one of those books one had to have on one’s shelves. My copy, now 30 years old, is still in place in my large art books section: its crumpled cover shows how much I have consulted it. By integrating non-Western art into the story, it represented a fresh perspective for students and soon became an unexpected bestseller. Possibly, however, Hugh Honour’s Companion Guide to Venice (1965) resonated more with me, as I carried it around on my first two or three visits to that city.

I knew nothing of the authors of A World History, certainly not that they lived happily together near Lucca for decades. The two had met in 1949, when Honour was studying English at Cambridge and Fleming, eight years his senior, was working as a solicitor. Deciding to put their lives together, they moved to the more tolerant atmosphere of Italy, where they made their permanent home. This is a charming memoir by a friend who was close to them throughout their lives there.

Susanna Johnston at 21 was certainly not untypical in having ‘no ambition other than a yearning to stay in Italy’. This required some kind of occupation, but it was a long shot when she was introduced to Percy Lubbock, widowed stepfather of Iris Origo, who was blind and grumpy but needed reading to. Johnston managed to win him over: she was able to take the place of the two young men who had kept him happy. They turned out to be Hugh Honour and John Fleming. They all became close friends before ‘the boys’ left for Asolo (Freya Stark provided a house for them) and then set up themselves up in an idyllic house, the Villa Marchio, near Lucca. This is a personal memoir and so there is little of their growing fame in the art world, something that surprised and sometimes irritated them both, especially when they had to be on show to receive prizes.

Johnston feared that she might offend them all by marrying and having babies but her husband, Nicky (the architect Nicholas Johnston), was already known to Hugh Honour and was accepted within the friendships. Eventually the Johnstons bought a house near Lucca and summers were spent in going to and fro between them. Johnston always had a shopping list to bring from London: ‘cigarettes, Charbonnel et Walker chocolates, double-edged razor blades, marmite and gossip’. Honour and Fleming, a normally fastidious pair, rather relished the wild behaviour of the Johnstons’ teenage daughters, who add memoirs of their own to this book.

Hugh Honour was ‘stately, anxious and polite’, frugal with money, (probably as a result of his father having been a bankrupt) and he could drive—somewhat wildly, while John Fleming could not—and had a dashing side that he kept confned to James Bond cigarettes and good restaurants. John was more gregarious and tactile and predictably furious with incompetent professionals. The reticent Hugh resented Johnston’s cosy chats with him. Once, when Honour had gone off to research in the US, Fleming joined Johnston’s family for the Rocky Horror Show. He was found out and there was a brief reciprocal froideur. Honour and Fleming were destined to be together, even to merge into one. Neither of them ever used the personal pronoun ‘I’. It was always, ‘We didn’t sleep very well last night’ and, ‘Our dentist is very pleased with our teeth’.

‘The boys’ knew all the leading figures of the Italian art world. Rudolf Wittkower and Bernard Berenson, of course, in their early days in Italy; James Pope-Hennessy, Francis Haskell and the classicist Michael Grant; but they were cautious in their friendships. They laughed cattily at the snobbishnesses of the aesthetes—Harold Acton at La Pietra in Florence (‘Too many photographs of royalty. He’s become obsessed with them. It will lead to a very lonely old age’) and were annoyed by those who stayed too long, distracting them from their work. ‘I have been busy sweeping up the names he dropped on the terrace all afternoon’, was Hugh Honour’s comment on John Calmann, the erudite but loquacious publisher of their books, who was tragically murdered the day after he left them. Comments were often waspish. On Henry Moore: ‘We think he was greatly overrated and probably ruined as an artist by Kenneth Clark, who we did NOT care for.’

Their working life consisted of Honour, the more scholarly of the two, ensconced for the day in his study, only emerging to cook for Fleming and any staying guest. It was John Fleming who wrote the chapters on architecture and was the organiser of the final text, with pictures and notes fitted in. Editors found them easy to work with but as they grew more famous, ‘rich, culture-craving elderly ladies wanted to visit them.’ They had become ‘one of the prescribed Anglo-Tuscan sights’; but these unknown visitors, whose chauffeurs gamely negotiated the rough road up to the villa, annoyed the pair and were cruelly much mocked after they had left them back in peace.

And then disaster struck. Returning from Bologna one day, they found that their house had been burgled and stripped of everything of value. The loss haunted them. Johnston scoured the antique shops for replacements but failed to find much of equivalent quality. John Fleming was never the same again and they both resented having to leave someone living there when they were away. Gradually, the long friendship changed as Fleming and Honour grew older and their villa ever more decrepit. Fleming’s sight began to worsen and he was reduced to listening to audiobooks. Then bone cancer set in. He faded away with Hugh devotedly looking after him.

Hugh Honour struggled on. There was a silver lining. Their lives had been enriched by two young antique dealers from Lucca, Carl Kraag and Valter Fabiani, who had become so close that Valter was named the heir. He dutifully adopted the role of son to Hugh and arranged help for him as his legs weakened. A sensitive and capable Sri Lankan carer and his family took over for the last months as the house disintegrated, flashes of light spurting erratically from disconnected wires and plugs. Despite the loss of much of his movement, Hugh enjoyed his Charbonnel et Walker chocolates to the end.

This book is a delight to read. It is an affectionate tribute to a deep and loving friendship, with the backdrop of Italy, food and art to add to the pleasure of reading it.

Reviewed by Charles Freeman, Historical Consultant to the Blue Guides.