As part of the Budapest Spring Festival, an unusual exhibition has come to the Budapest History Museum: “Painters in the Mirror”, a display of self-portraits by Hungarian artists from the collection of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. The Uffizi has an extensive collection of self-portraits, the largest in the world: over 1,600 of them, of which 24 are of Hungarian artists. They are displayed in the Corridoio Vasariano, a covered walkway built by Vasari in five months to celebrate the marriage of Francesco de’ Medici and Joanna of Austria in 1565. Nearly a kilometre long, its purpose was to connect Palazzo Vecchio via the Uffizi and Ponte Vecchio with the new residence of the Medici dukes at Palazzo Pitti. The Medici family found it particularly convenient in wet weather and it was sometimes used as a nursery for the children of the grand dukes. Elderly or infirm members of the family were wheeled along it in bath chairs. The Uffizi’s collection of self-portraits has been hung here since the early 20th century. The collection was begun by Cardinal Leopoldo in 1664. Having acquired the self-portraits of Guercino and Pietro da Cortona, he went on to collect the ‘selfies’ of some 80 more artists. The collection continues to be augmented.

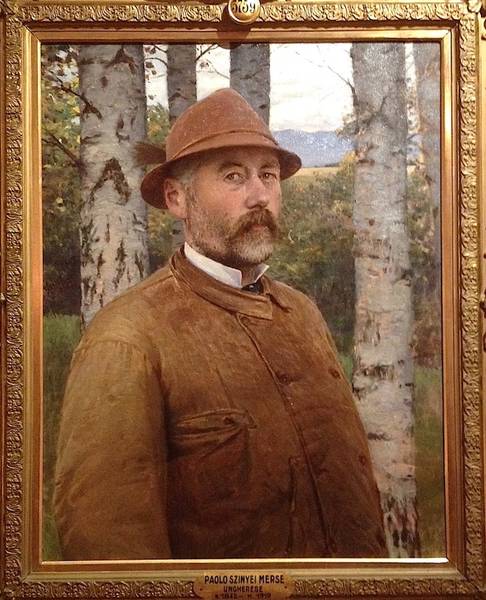

The first Hungarian self-portrait to enter the collection was that of the elder Károly Markó, a painter of almost Claude-like landscapes who settled near Florence in 1848. The collection continued to expand throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, largely by invitation. The portraits of Rippl-Rónai, István Csók and Pál Szinyei Merse arrived at the Uffizi by this route. The great painter of large-scale historical canvases Gyula Benczúr was also invited to contribute a self-portrait and produced one expressly for the Uffizi. Other self-portraits were acquired by purchase. It was not long before artists eagerly sought to have themselves represented at the Uffizi, and the gallery received numerous offers, some of which it accepted and some of which it did not. Miklós Barabás, considered (at least in Hungary) one of the finest portraitists of his day (1810–98), submitted a portrait (it was submitted, in fact, by his son-in-law) but it was not considered by the board of judges to be of sufficient artistic merit. It was not returned, however, and is still the property of the Italian state, officially entered in the Uffizi’s inventory. It forms part of the current exhibition, hung alongside a charming likeness by Barabás of a young woman in a black dress, painted against a backdrop in the Hungarian—and Italian—national colours of red, white and green.

Self-portraits of Hungarian modern and contemporary artists include Victor Vasarely’s typically optical-illusory upside-down image of himself, and a fine work by László Fehér (b. 1953), who presents a typically hyper-realist image of himself in a small pocket mirror.

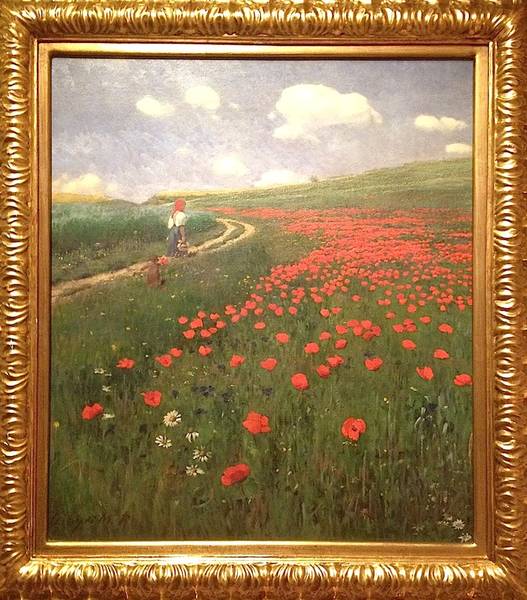

Each self-portrait in this interesting and absorbing small exhibition is shown alongside another painting by the same artist which may be taken to be representative of his or her oeuvre. Some of the more memorable pairings include Philip de László’s classic, textbook self-portrait hung next to his stunning likeness of Pope Leo XIII; and Pál Szinyei Merse’s view of himself in a wintry birch forest hung alongside his beautiful Poppy Field, its tall grass and cotton-wool clouds redolent of early summer warmth.

“Painters in the Mirror”, at the Budapest History Museum, runs until 20th July. The collection of the Uffizi is covered in detail in Blue Guide Florence.