I am not quite sure how my 1961 edition of Pevsner’s Suffolk has survived long enough still to be found among the debris in the boot of my car. It surfaces and resurfaces as if carrying the persistence of its author with it. It is a paperback edition and I must have brought it when I was cycling round Suffolk churches for a school project in the summer of 1965. I was intrigued to read in this meticulous and absorbing account of Pevsner’s life that he was upset when later volumes only appeared as pricey hardbacks so depriving one of his target audiences, school children, of accessible copies. I was one of the lucky ones.

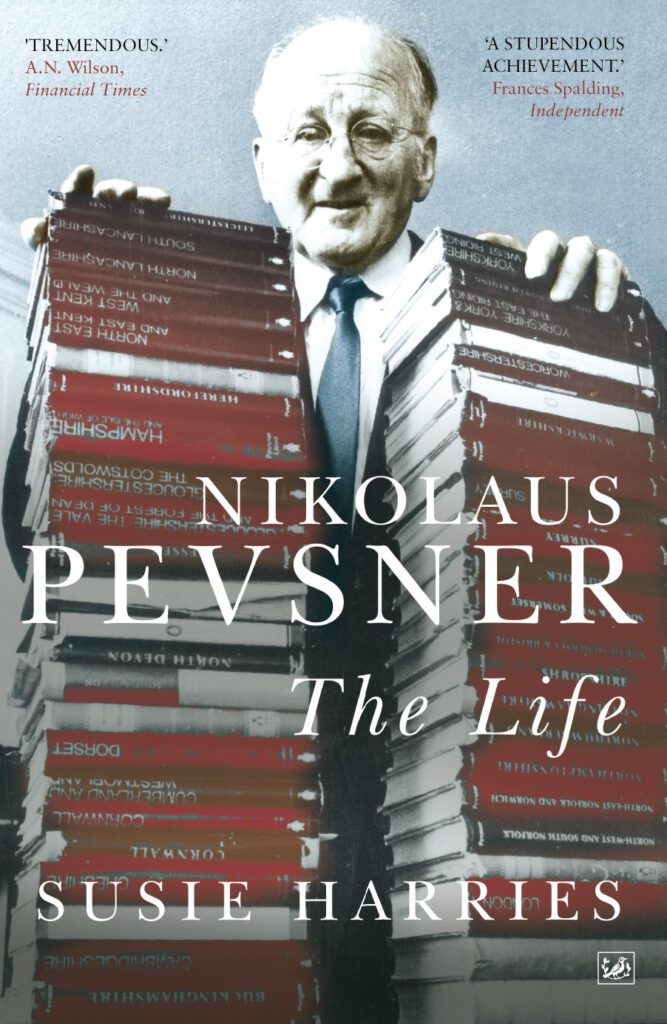

Pevsner is, of course, the acclaimed guide to The Buildings of England, eventually, with some help from collaborators, covering the whole of the country in forty-six volumes. The elderly, and—as Harries tells us, exhausted, author, gazes benignly at us over his achievement, here piled in two columns on the front cover. It is to Pevsner that one turns to check whether a church window is ‘Perp’ or ‘Dec’ and I was always rather proud that he had ventured far enough up the drive of my family home in Suffolk to note its ‘porch with Roman Doric columns’, although, alas, his date for the exterior, early 18thcentury, is wrong; the façade was remodelled in the 1830s. In his old age Pevsner relaxed enough to admit he had made many such mistakes in his rigorously disciplined forays into the countryside.

Of course, one reads Pevsner for his pithy comments. One of my favourite local churches in Suffolk is Dennington but Pevsner sternly brings my enthusiasm to order by telling me that ‘Piscina and sedilia are strangely and perversely arched’ and that ‘the chancel arch is painfully incorrect’. It is a style that is utterly distinctive but often limited and I was glad that Harries put me onto another, fuller, work of his, The Leaves of Southwell [Minster]—a King Penguin of 1945 but easy to track down online—where he enthuses over the perfect marriage of stone and nature in the Minster capitals. An extract was read at his funeral.

This biography is wonderfully comprehensive. When Pevsner left his lectureship at Göttingen to seek a new life in England in 1933, he brought the intense analytical tradition of German art history with him and Harries covers this well. Pevsner was conservative by nature and sympathetic to the demands for order in Germany but never, as has been suggested in a recent, less rigorous biography, a Nazi (Harries has the advantage of sole access to his family archive, so she can provide an accurate picture). We can understand why he found the English tradition of connoisseurship gleaned from weekends nosing as a guest around country houses amateurish, but he persevered and eventually found his niches lecturing (at Birkbeck and later as Slade professor at Cambridge), advising, broadcasting (the Reith Lecturer of 1955) and writing. He was utterly professional and endlessly assiduous in accumulating architectural details. Of course, to some, this meant that he missed or ignored the human side of building. His personality, often removed and abrupt, reflected his dedication and one can understand the difficulties he experienced in his marriage with the more gregarious Lola, who suffered his long absences, self-absorption and occasional dalliances with other women. He missed her most, of course, when she died suddenly in 1963, twenty years before he did.

Outside his Buildings of England, Pevsner was perhaps best known for his championship of the Modern Movement, notably in his Pioneers of the Modern Movement, an early English work of 1936. He argued that ‘good’ modern building should reflect function, materials should not be disguised and lines should be clean without ornament. Then he was drawn into the revived interest in Victorian buildings and so became a founder of the Victorian Society (where he had to face childish ridicule for his ‘Germanic’ approach from one John Betjeman). Balancing the demands for new buildings against the varying qualities of older ones involved him in endless and often fruitless battles with planners, architects and developers alike. Pevsner was never a people person but his vast knowledge and persistence earned him increasing respect. His taste and approach could always be criticized, of course, and there were always some whose ripostes to his enthusiasms were malicious rather than scholarly. However, he held to his own vision and avoided feuds. By the end of his life the honours were flowing in profusion from across the world.

It is always hard to deal with the austere who say little about their emotions and who lose themselves in dedicated scholarship. The work can easily swamp the individual. Pevsner needed and deserved a full biography and this could hardly be bettered. Thanks to her ferreting through the family archives, her judicious sympathy for her subject, and her scholarly accounts of the academic background, Susie Harries brings to life the man who has left us an awesome legacy. Wherever we are, in any part of England, we still need to ask of an interesting building: ‘Is it in Pevsner?’

Reviewed by Charles Freeman, historical consultant to the Blue Guides and author of Sites of Antiquity: 50 sites that Explain the Classical World . His Holy Bones Holy Dust, a study of the medieval cult of relics, is reviewed here .