Ingrid D. Rowland, From Pompeii: The Afterlife of a Roman Town, Harvard University Press, 2014.

One of the pleasures of reading The New York Review of Books is coming across the articles by Ingrid Rowland. Professor Rowland teaches at the University of Notre Dame in Rome and specialises in art history and cultural relationships, especially those between Italy and its Classical and Renaissance past. She always had something interesting to say and it is perhaps because I have happy memories of sitting around in Rome with archaeologists and art historians that I find her especially engaging.

In the introduction of her enjoyable survey of Pompeii’s after-history, we see the eight-year old Rowland, pig-tailed and bespectacled, on her first visit to the ruins in 1962. The experience clearly resonated with her (never underestimate where the experiences of an eight-year old might lead!) and she now teaches permanently in Italy. From Pompeii is the story of the characters who were fascinated by the drama of Vesuvius, its eruptions and the vanished communities of Herculaneum and Pompeii as they were slowly recovered from the lava. For centuries, legends had persisted of buried cities but there was nothing to be seen. Instead the fascination was with Vesuvius. Athanasius Kircher, would-be decipherer of hieroglyphics, a priest always on the edge of disfavour with the Church on account of his belief in the natural rather than miraculous background of geological events, gave pride of place to the inner workings of the volcano in his influential work Mundus Subterraneus, ‘The Subterranean World’ (1665).

A hundred years later the treasures of Herculaneum and then Pompeii were beginning to emerge and were firmly fixed in the itinerary of the leading cultural figures of the day. Rowland describes the reactions of the young Mozart, Charles Dickens, Mark Twain and Renoir, not only to the ruins but to the bustling, poverty-stricken street-life of Naples. For 19th-century romantics in Russia, the painter Karl Bryullov’s epic The Last Day of Pompeii gripped the imagination as much as Edward Bulwer Lytton’s novel The Last Days of Pompeii did of those in Britain. A special accolade is due to the Puglian Bartolo Longo who embarked on creating a new Pompeii on the edge of the old, around a church of the Madonna of the Rosary. A damaged and ugly painting of the Virgin Mary, brought to the church on a dung cart, proved an unlikely miracle-worker and soon the trains that brought tourists to Pompeii were filled too with pilgrims. Longo energetically ploughed back their donations into the crime-ridden and impoverished neighbourhood and parts of his ‘new’ Pompeii survive.

Rowland enjoys her digressions. The blood of St Januarius (San Gennaro) has an important role to play. Every year it miraculously liquefies on three separate occasions—except when it doesn’t, in warning of impending eruptions of Vesuvius. Then there is the phallus of Priapus from the House of the Vetii: guides in charge of prominent visitors such as Hillary Clinton and her daughter Chelsea scurry past it in haste so that no compromising photos can be snapped. There is space too for the bizarre cult of the Fontanelle, the skulls preserved in caves under the city of Naples and which, while their owners languish in Purgatory, are supposed to have miraculous powers of intercession.

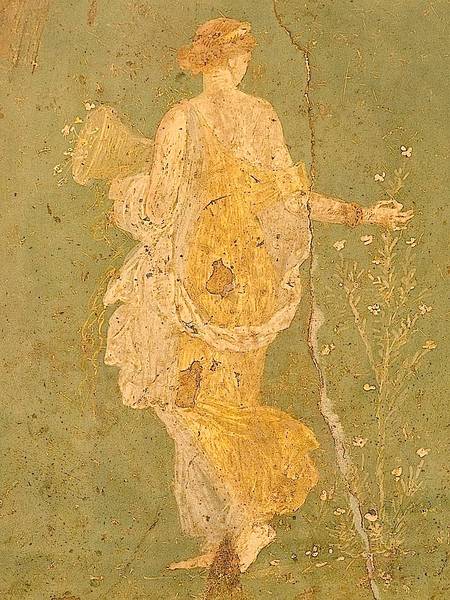

However, the ruins always form the backdrop to the digressions and Rowland relates the exploits of the famous curators. Guiseppe Fiorelli, appointed in 1848, replaced treasure-hunting pits with carefully stratified excavations. His calchi (plaster casts) shifted attention to the human victims of the eruption and still provide some of the most moving testimonies to the drama of AD 79. It was Fiorelli who kept wall-paintings in situ where they were found, rather than prising them off for the royal collection. Politics met with archaeology when Superintendent Vittorio Spianazzola, an opponent of Fascism married to a Jewish scholar, was removed in 1924 and replaced by Amadeo Maiuri, who dominated the Pompeiian scene until 1961. His use of mechanical diggers exposed large parts of the city but left it impossible to maintain. I despaired, as Rowland does, over the crumbling remains. On my most recent visit to Pompeii two years ago, many of the houses were closed off. Just ten years earlier there had been more to see. Even a campaign to round up stray dogs stagnated as the available funds were embezzled. Herculaneum is now much more welcoming.

And no less ominous than the slow decay of Pompeii is the ever-present threat of a fresh eruption of Vesuvius. The last was in 1944 and it is time for it to blow again. Rowland is doubtful whether the anarchic inhabitants of the Bay, long used to outwitting authority, will submit to the evacuation plans. The blood of St Januarius will no doubt liquefy if there is nothing to fear—but if it stays solid, an early escape will be well advised. If by chance I am caught there among the fleeing residents, I shall seek refuge on a Gran Turismo bus, its hurried entry and exit from the region long perfected by the demands of whisking tourists quickly around the site and back through the traffic jams in time for dinner in Rome.

Reviewed by Charles Freeman. Pompeii, Herculaneum and Naples are covered in Blue Guide Southern Italy. Pompeii is one of the 50 sites in Freeman’s Sites of Antiquity.