In Istanbul, on the north side of Divan Yolu, the street that follows the course of the Mese or ‘Central Way’ of old Constantinople, stands a decayed porphyry stump known as Çemberlitaş, the ‘Hooped Column’. In its heyday it would have been much more splendid, for it was, according to Blue Guide Istanbul (6th ed. 2011), ‘erected by Constantine to commemorate the dedication of the city as capital of the Roman Empire on 11th May 330. It stood at the centre of the Forum of Constantine, a colonnaded oval portico adorned with statues of pagan deities, Roman emperors and Christian saints, and thought to have been the inspiration for what Bernini later built in front of St Peter’s in Rome.’ What is also interesting about the column is the statue that would have crowned it, a colossal likeness of Constantine as Sol Invictus, the Unconquered and Unconquerable Sun, with the orb of the world in his hand and a crown of brazen sunrays glittering on his head.

In his Hymn to God the Father, John Donne makes use of a popular metaphysical pun:

…swear by Thyself, that at my death Thy Son

Shall shine as he shines now…

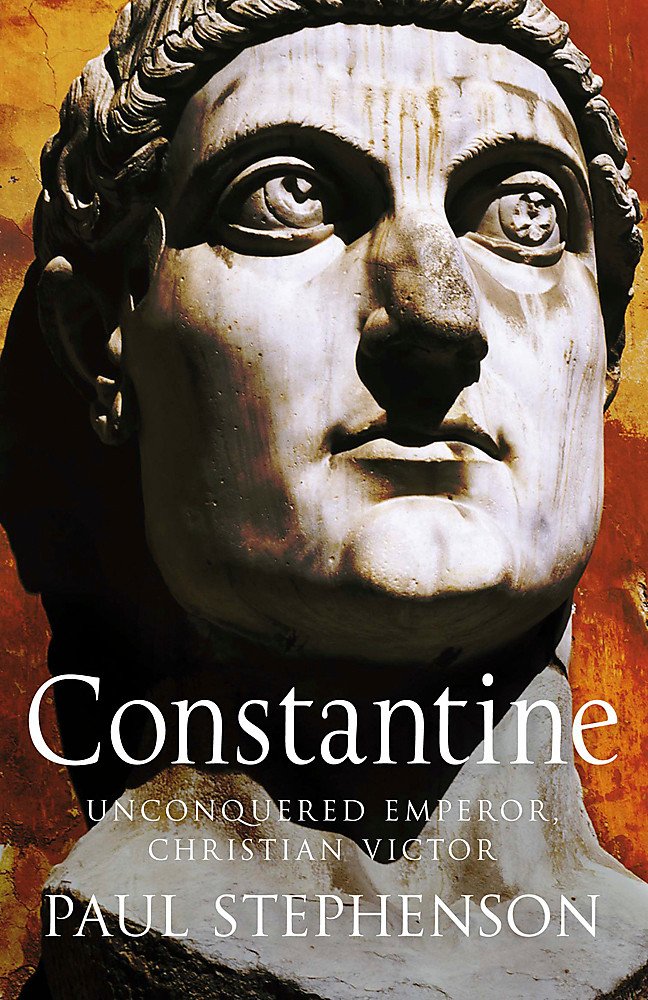

The transference of pagan sun of the heavens to Christian son of God, victorious over death, is something that happened long before Donne’s time. And Constantine’s adoption of the sun/son cult and his public portrayal of himself as brazen victor were significant and deliberate—at least Paul Stephenson thinks so. But why? Was it because he was sincere in his Christian faith? Or was it simple political expediency? Biographies have been written that seek to prove both these theses. Stephenson’s argument is slightly different. Constantine’s devotion to Christ is not what turned Christianity into the majority faith of the Eastern Empire. He is neither the hero that the partisan Christian historian Eusebius sought to portray (4th century) nor the villain that the apostased Catholic convert Edward Gibbon depicts (18th century), with sour scorn, as using ‘the altars of the church as a convenient footstool to the throne of the empire’.

Instead, Stephenson focuses on something else: the army. Constantine grew up in an age when emperors were raised high and then capriciously felled by their barracksmen. The military had enormous power, which, in the right hands, could be cleverly channelled. For Stephenson, Constantine used the army as the driving force and ‘chief instrument of his political will’, aggressively adopting the Victor persona, something which the army accepted wholeheartedly because of what Stephenson calls the ‘established Roman theology of victory’. After the decisive Battle of the Milvian Bridge, when Constantine defeated his rival Maxentius and sent him to his death in the Tiber waters, floundering helplessly in his heavy armour, the bringer of that victory was Christ. We need not trouble ourselves with how, with whether Constantine really did have a vision of a Cross. The fact is that from then on it was Christ and not Zeus or Sol who became the emperor’s patron deity and it was under Christ’s banner that the imperial legions fought.

Constantine’s mother had been a Christian but the world into which her son was born was a pagan one. Christ, like any other god, was a divine being to be flattered and appeased. Constantine’s devotion to his god was not that of a pious Christian as we would understand the term today. Nor was it simply a cyncial political stunt. The truth falls somewhere in between, and Constantine’s reign is, Stephenson thinks, ‘a case study in the interaction of faith and power.’

Readable and convincing, the book presents a portrait of a great soldier and propagandist, a man who believed his earthly power and success were due to the intervention of the god of the Christians. Thus it was that he adopted that cult as his personal totem. He certainly never heard or believed that the meek were blessed and would inherit the earth.

Reviewed by Annabel Barber