Easter always marks the moment in the year in Italy when there are the most visitors: from then the crowds will remain a fixture until midsummer. So a visit to Venice in these first spring days can be all the more rewarding.

But at any time of year there are campi which always remain truly Venetian, and one of these is the large Campo San Giacomo dell’Orio which almost entirely circles the church of the same name in the sestiere of Santa Croce, not far from the railway station. It is a place where the locals sit and talk on the benches scattered here and there under the few trees, and the children come to run about and play games. Indeed on sunny afternoons, when you enter one of the several doors into the church, you will often find a child playing hide-and-seek in the porch or hear the crash of a football against the exterior, and the sound of the fun taking place outside is always present. But this only makes the church an even more delightful place to explore, and there are plenty of reminders that you are in the House of God, especially in Lent when some of the works of art are shrouded in purple cloth, a tradition once found in the churches all over Italy. Perhaps the church’s greatest treasure, the Crucifix by Paolo Veneziano (1324), with its painted terminals intact, cannot, therefore, be seen in this period: it still hangs in the apse but is a dramatic sight totally hidden from view by a drape which will only be pulled off on Easter morning.

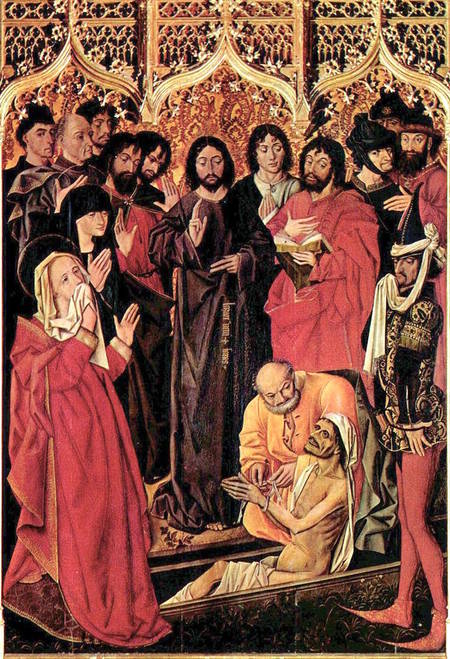

There is an extraordinary variety of beautiful sculptures, paintings, and architectural features preserved in every nook and cranny of the church. Statues of the Madonna abound: a Byzantine statuette shows her holding a spindle, having just risen from her chair; there is a very ruined little Virgin orans in a niche; she carries a (now headless) Child in another little carving which has echoes of French medieval works; and there is a large painted wood statue of her from a few centuries later. The main altarpiece on the apse wall is a Madonna Enthroned with Saints, a typically eccentric work by the great painter Lorenzo Lotto. Also in the sanctuary, set in to the walls, are two marble inlaid Crosses, particularly unusual for their large dimensions. The painter whose works can be seen in almost every church in Venice, Palma Giovane, can be particularly appreciated here, from his large horizontal canvases in the Chapel of the Holy Spirit, and those, even larger, in the aisle chapels (including the Multiplication of the Loaves and Fishes and the Martyrdom of St Lawrence), to his cycle of paintings made to decorate the entire Sacrestia Vecchia in 1581. In the same year Palma Giovane’s much more famous contemporary Paolo Veronese painted the altarpiece in a chapel close by, of three saints, which features a lovely little putto above flying down towards them bringing their martyr’s palms. The Sacrestia Nuova (which has a ceiling painting by Paolo Veronese) is a veritable little museum of paintings, one of which, by Francesco Bassano, includes portraits of the painter’s family as well as Titian sporting a red hat, all of them in the crowd listening to St John the Baptist preaching.

The architecture of the church is also noteworthy, from the typically tall detached campanile dating from the 13th century to its wonderful wooden ship’s keel roof, installed in the following century. There is a rare shiny green marble column traditionally thought to have come from Solomon’s palace, but in any case dated to the 6th century, and a delightful Greek cipollino marble font (probably very ancient) by the west door provided with a little marble ledge for a child to sit and recover after its total immersion. The paintings by artists from the Veneto across the centuries include one of the best works of Giovanni Buonconsiglio (Three Saints, 1498), and, from the 17th century, works by Giulio del Moro, Padovanino, and Schiavone. A painting of the Madonna and Saints is a typical work by Giovanni Battista Pittoni, dated 1764.

I always try to come back to San Giacomo dell’Orio whenever I visit Venice, even though it never needs ‘up-dating’ for the Blue Guide Venice. The church stays open all day (7.30am to 7pm) and the two sacristies are shown on request by volunteers from 8.30 to 4.30 pm (unless they leave a note on the door that they have slipped out for a quick lunch or a coffee).

by Alta Macadam