This October it will be 500 years since Luther made public his famous 95 theses in Wittenberg. The anniversary is being celebrated on the web, by a pilgrimage and festival, with events in and around Wittenberg itself, as well as in print. In Budapest, the Hungarian National Museum has devoted an exhibition to the subject of the Reformation in Hungary: Ige-idők (Grammar and Grace), which runs until November 5th.

The displays open with a huge black and white reproduction of a Last Judgement scene, as an illustration of the late medieval mindset. The world is presented as a place beset by sin and temptation. When the final trumpet sounds, the good will be rewarded and the wicked punished. Altarpieces of the northern European school reinforce the point–and make it clear that the only hope we have of navigating the journey successfully is by bargaining and mediation. God’s Word is our guide, but it comes down to us in Latin, a language we do not speak, so His message has to be transcribed pictorially, through stories of Christ and the exemplary lives of the saints. We cannot communicate directly with God, so the saints intercede for us, helping us to achieve salvation. This will never be attained without the purifying fire of Purgatory; the tools for getting out quickly are faith and good works, but because these are notoriously unreliable currency, we are offered the chance to pay, through the purchase of indulgences.

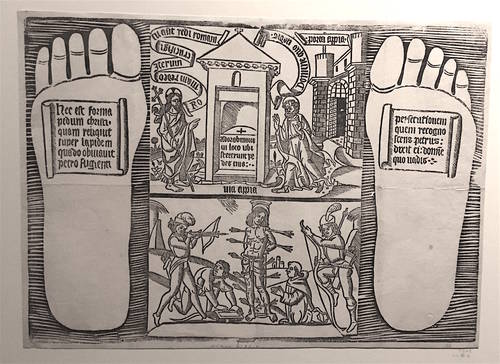

This, in a nutshell, is the pre-Reformation Christian world. Mysterious, untransparent, trammelled by an unwieldy bureaucracy of saints, and, as an inevitable result, corrupt. The first room spends some time presenting Rome as the arch culprit. It is Rome that allows the system of indulgences. Rome also wilfully misleads her flock. This is illustrated by a woodcut of two feet. As a piece of evidence to support the curators’ point it is well chosen. The footprints are those that occur on a crude stone block preserved in the church of San Sebastiano fuori le Mura on the Via Appia in Rome. They purport to be the imprints left by Christ’s feet as he appeared to St Peter, who was fleeing the city in an attempt to avoid martyrdom. It’s a charming story but the footprints are a blatant fake, precisely the sort of hoaxing that the 16th-century Reformers aimed to root out.

Background information is presented through a series of wall banners. The texts are long and I would have appreciated somewhere to sit down while reading them. The exhibited objects themselves (some of them never exhibited before) are captioned erratically, sometimes with a translation (but more often not, so visitors with no Hungarian will struggle). These are quibbles, but it makes the information difficult to digest.

The English title of this exhibition, Grammar and Grace, has a good alliterative ring. But the Hungarian can also be translated as “The Age of the Word”; and it is really this that the exhibition is about, because it is through the Word (of God, transmitted to man in comprehensible form) that the Reformers sought to do their work. Whether salvation is achieved through faith or through works, or, as Luther had it, through grace alone (or only by grace), is a theological debate that the exhibition does not wrestle with. It concentrates on Protestantism’s fixation with text and the way text replaced images.

Altarpieces cease to be the principal tool of communication and what we get instead are books. A number of early Bibles and prayer books are exhibited, for example the Greek and Latin translation of the New Testament by Erasmus (Basel, 1516), intended as a basis from which vernacular translations could be made, translations which would make the phalanx of intermediary saints redundant, as Holy Writ was rendered in the common language of men. Men speaking the common tongue quickly became the problem. In early 16th-century Hungary, ecclesiastical leadership was in crisis. Many prelates were also military commanders and most were wiped out at the Battle of Mohács, the great Ottoman victory of 1526. Into the void stepped itinerant preachers, spreading the ideas of Luther and Calvin.

A wall banner notes that none of the achievements of the Reformation could have been accomplished without zeal. The examples of early Bibles, though–however remarkable–cannot speak to us in the way the altarpieces do. Deprived of the personality of the preachers who used them, these tomes struggle to convey the quality of this zeal. Some of the preachers will have been ardent and inspirational, opening up whole new realms of spirituality for their hearers. Others will have been fanatics, banishing imagination, insisting on the literal.

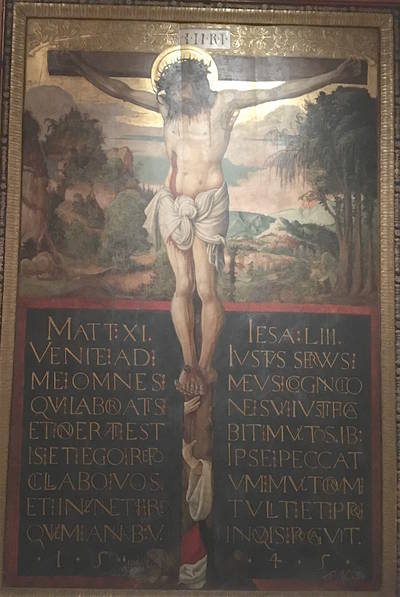

Text comes not only in the form of devotional books, which after all were rare and expensive (the early, 16th-century Bibles were mainly for the use of the preacher; copies for individual study took another century to arrive). Instead, altarpieces were redeployed as vehicles for the Word. Suddenly they are awash with writing. The exhibition has found a brilliant example: a 1519 Crucifixion altarpiece from Sibiu (Hermannstadt/Nagyszeben) in Transylvania, which was painted over in 1545 by the first Protestant minister. The entire lower section, which would have shown mourners at the foot of the Cross, has been overlaid with texts from St Matthew’s gospel and the book of Isaiah. Mary Magdalene’s hands can still just be seen in the central strip, clutching the Cross.

Translation, however, had its drawbacks. Just as the Internet is today, so the invention of printing in the Reformation era was a disruptive technology. Suddenly, vernacular Bibles were everywhere, being used by individual preachers with their own individual interpretations of God’s message. It was difficult to enforce an official line. In Reformation Hungary there were no burnings at the stake; instead different denominations co-existed. This seems to have been especially true because of the power vacuum created by the Ottomans, with their semi-tolerant approach and their appetite for tribute money. The town of Debrecen, for example, paid tribute in exchange for being left alone: it existed as a Christian republic, a ‘new Jerusalem’ on the Geneva model, referring to itself as Christianopolis (it remained self-governed in this way until the mid-1750s). That was the stronghold of Calvin. Both the Calvinist (Református) and Lutheran (Evangélikus) churches took root in historic Hungary. But the two reformers were very different temperamentally. The difference is nowhere better illustrated than by the pavement slabs in nearby Kálvin tér, close to the National Museum building. Here, underfoot, the flagstones are inscribed with quotations from Protestant theologians. “God in his mercy denies to his own what of his wrath he permits to unbelievers,” says Calvin stoically. Luther is more mischievous and less austere: “If I believed that God had no sense of humour, I would not want to go to Heaven.” The fathers of the Reformation did not sing from the same hymn sheet (Calvin didn’t sing, for a start).

Today we worry about fake news. During the Reformation people worried about free interpretations of scripture. In another 15th-century Sibiu altarpiece (here shown in an early 20th-century copy), Protestantised in 1650, Christ is shown behind bars at the bottom. St Jerome’s Vulgate Bible springs to mind (Lamentations 4:20), where his Latin translation makes mention of “Christ the Lord” a captive of our sins, something the original does not exactly say. If St Jerome could do it, what might a provincial pastor do? Inevitably there had to be a clampdown.

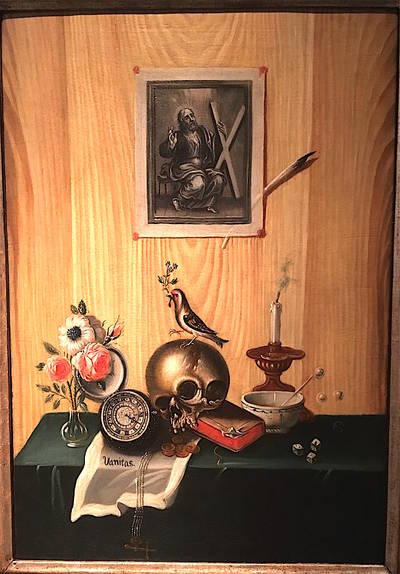

As surely as Catholicism ever did, Protestantism begins to use the tools of propaganda. The result is a kind of sententious, moralising religiosity, as exemplified by the Dutch-inspired 18th-century Vanitas still life by an unknown Hungarian painter. All the stock elements are there, to indicate the transience of this worldly existence: the skull, the snuffed candle, the soap bubbles, the dog-eared book, the fading flowers. Fickle fortune is indicated by the dice. False riches by the coins. The only thing that can save us is Christ and the Spirit, symbolised by the goldfinch.

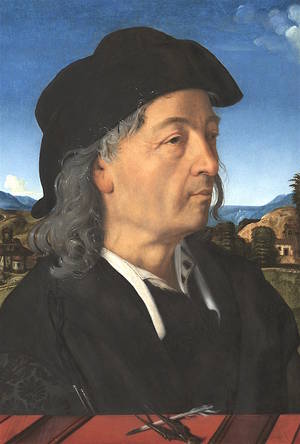

Inevitably, as it becomes established, Protestantism also enters the realm of politics. In Hungary’s case this was particularly true in Transylvania, but after Joseph II’s Edict of Tolerance (1781), it becomes true in general. Protestants also make significant contributions to science (understandably) and the arts. The vernacular Bible in Hungary was influential in shaping language and thus thought. But the Reformation as a lathe on which identity is shaped also brings with it identity politics. If a Reformation brings choice, then one has to self-identify. No longer can we talk of one people under the imperial aegis of a pope or a Habsburg monarch, but separate nations of denomination, each with its own belief systems. Public expressions of religion have elements in common with modern virtue-signalling. In the end, much comes down to personal preference and inclination. It is difficult not to return to the first room, as the one where the objects speak most freely to each beholder. There is a lovely panel showing St Martin (illustrated at the top of this article). The bishop saint, with a huge gold halo, stands before an altar raising the Host aloft as angels drape his naked arms (naked because he has charitably given half his cloak to a beggar). In the background, in a doorway, stands a man, observing the scene just as we do, but from the opposite side. It is a lovely and subtle work of art, linking God and Man. What better way to communicate mystery and transcendence?

Some of the early altarpieces in this exhibition now seem modern in a way that many of the later, once-revolutionary artefacts do not. Bibles, prayer books and orders of service, once translated, are in need of constant revision, as language, society and its values change. A little columbarium vitrine in the penultimate room contains quotes from modern authors. The one from Péter Esterházy sums it up: “The spectrum of language is not only spatial but temporal. Words have their time, or, to put it another way, time lies couched within words. Our time, the time of those who use the words, our history, our very selves.” A reformation which puts mysteries into words sets itself on a path of perpetual re-reform as the words date and lose their revelatory power.

That does not mean we should not reform. But how should reformations be conducted? How can we prevent them either from degenerating into riot or from fossilising into the very sclerotic structures they sought to sweep away? This exhibition poses all these questions. It is extremely thought-provoking. How far have we actually come in the half-millennium since Luther railed against Tetzel?