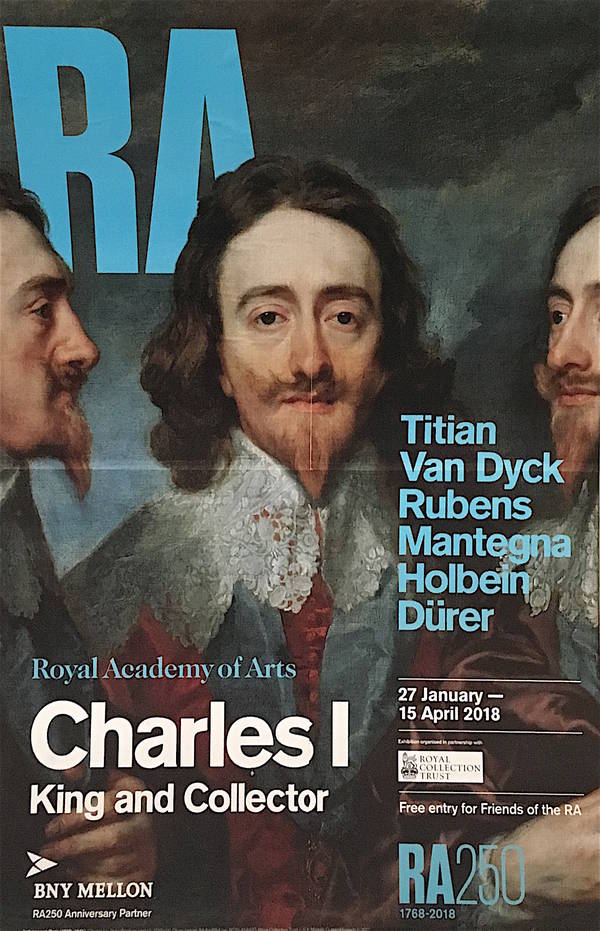

This magnificent display of Old Master paintings from the royal collection amassed by King Charles I, many of them reunited for the first time since the mid-17th century at the Royal Academy in London (running until mid-April) has been met with frenzied enthusiasm. And rightly so. There are some stunning works on show here, by Titian, Veronese, Mantegna, Correggio, Holbein, Rubens, Van Dyck and others. Many of them are from the Royal Collection. Others are from the National Gallery, London. Still others have been borrowed from international collections, to which they made their way following the Commonwealth Sale after the beheading of Charles I, when his collection was dispersed (from 1649).

Charles I, as is well known, was frail and diminutive of stature but magnificent in his own conception of what kingship meant. His ideas about the Divine Right of kings were to be his undoing: he met his death by beheading in January 1649. While alive, Charles made full use of his own image to create an iconic status for himself as God’s appointee. In Britain he was the first monarch to do this. With the aid of his court painter, Anthony Van Dyck, who was appointed to the position in 1632, he drew on Classical models, derived from the painting and sculpture of Renaissance Italy, to create an awe-inspiring image of a ruler somehow superhuman. Superhuman but not remote. Just as Roman imperial statuary was impressive in its ability to portray a natural likeness, so the portraits of the king and his family by Van Dyck show a real man, inhabiting and dominating the picture space in regal fashion, but a flesh and blood mortal nonetheless.

The paintings here, though ‘reunited’ in a sense (King Charles exhibited them throughout his palaces and the two great equestrian portraits of the king in armour would never have hung side by side in his lifetime as they do now in the Royal Academy Central Hall), cannot, in the exhibition space offered by the RA, replicate the effect they would have produced when seen at the end of carefully contrived vistas at Whitehall, for example. What they do show is the way Van Dyck, inspired by Rubens, reached constantly back into the world of the north Italian Renaissance (and through that, back into antiquity) for iconographical models to convey divinity and power. These models were made available to the artist by his royal patron, who bought wisely and well, with the express aim of setting up a collection to rival those of the great courts of Europe. His desire to do so appears to have been kindled during a visit to Spain in 1623, in an attempt to secure the hand of the Infanta Maria Anna. The marriage negotiations failed but the young prince had seen the magnificent portable trappings of the Spanish Habsburg court and his baggage train on his journey home to London creaked and groaned with masterpieces by Titian and Velázquez. After 1627, when the House of Gonzaga, rulers of Mantua, became extinct in the male line, Charles purchased the bulk of the family’s stupendous collection, which included masterpieces by Mantegna (the Triumph of Caesar cycle) and Correggio (The School of Love, which fetched a particularly good price in the Commonwealth Sale. Young men loved Correggio’s semi-suppressed salaciousness).

Rubens, who first visited London in 1629 on a peace-keeping mission from Spain, was to dub King Charles ‘the greatest amateur of paintings among the princes of the world’.There are many highlights in this show. To choose just two, it would be Titian’s Supper at Emmaus (c. 1534; sold for £600 in 1651, now in the Louvre), a magnificent scene with calm mountain peaks of the Veneto dolomites in the background and a cat and dog duelling under the table; and the deliciously self-satisfied self-portrait by Van Dyck, in which he looks complacently out at the viewer, holding up the gold chain that he received upon his knighthood in 1632, and pointing with his other hand at an outsize sunflower, surely a symbol of gilded royal patronage.

This is a triumph of a show, not least for the extraordinary borrowing power it demonstrates. Many of the works on display here are not readily lent. It also reminds us how intrinsically interlinked are all the strands of human endeavour and human progress. There has always been a great symbiosis between artists, of course. Antonello da Messina was influenced by Netherlandish painters. Dürer was influenced by Bellini. Without the great allegorical celing paintings of Venice, by Veronese and Tintoretto, or of Rome and Florence by Pietro da Cortona, or of Parma by Correggio, could we ever have had the Banqueting House in London by Rubens? Not likley. And the art of Rubens was brought to foggy Albion by Charles I. The canvases he painted for the ceiling of the Banqueting House at Whitehall Palace, between 1629 and 1630, celebrating the power and wisdom of Charles’ father and predecessor James I and culminating in the apotheosis of the monarch, had brought allegory, monumentalism, grandeur and godliness to the art of Britain. It came to a squalid end. It was through a window of that very Banqueting House that Charles I climbed onto the scaffold. His cosmography, his taste, his spirit and his vision were extinguished at an axe-stroke.

Reviewed by Annabel Barber