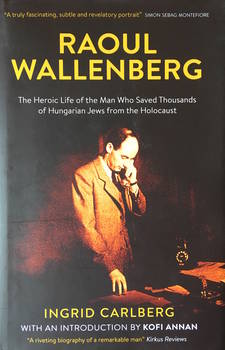

Ingrid Carlberg: Raoul Wallenberg: The Heroic Life of the Man Who Saved Thousands of Hungarian Jews from the Holocaust. Translated Ebbe Segerberg. Maclehose Press, 2016

The name of Raoul Wallenberg is well-known in Budapest today: there is a street named after him; two statues stand to his memory; and there is a general awareness that he was a brave individual, a Swede honoured as Righteous Among the Nations for his resistance to Nazi genocide. But who was he more exactly? This excellent biography, painstakingly assembled from interviews and written primary sources by the Swedish journalist Ingrid Carlberg, is now available in a clear and lively translation. It gives an excellent insight into the man and his times. Balanced and informed, it largely avoids the pitfalls of sermonising or anguished hand-wringing, leaving calmly-presented facts to tell the story much better.

Wallenberg was born shortly before the First World War. His father, who died two months before Wallenberg’s birth, was a scion of a Swedish banking, shipping and manufacturing dynasty. The young Wallenberg might well have expected a place in the family business, particularly as his grandfather aimed to school him for precisely such a role, sending him to study in the US and finding work placements for him in South Africa and Israel. This exotic (by the standards of the time) upbringing, coupled with the fact that his uncles never did deliver on a position in the family firm, led Wallenberg to various schemes and ventures, and, from 1941, a directorship in the Mid-European Trading Company, jointly owned by Swedish shipping magnate Sven Salén and Swedish-resident Hungarian émigré Kálmán Lauer. The company engaged in “importing eggs, fowl and tinned goods”, among other things, mainly from Hungary.

By 1943 Nazi Germany’s genocidal ambitions and extermination of large numbers of Jews were becoming clear to the outside world. For the Allies, this was another compelling reason for doing everything to hasten the Third Reich’s defeat. Roosevelt’s World Refugee Board, established in January 1944, assembled a huge budget to aid and save Europe’s Jews. Wallenberg was well-qualified to be the WRB’s man in Budapest: he had visited the city frequently and had a considerable network there—and by coincidence, the Mid-European Trading Company had offices in the same building as the US Embassy in Stockholm. An embassy official who met Lauer in the elevator asked him to recommend “a reliable, energetic and intelligent person” for the post. But what made Wallenberg accept? As Carlberg asks, what makes an act heroic? A contributing factor might have been Wallenberg’s attendance at a secret screening, at the British Embassy in Stockholm, of the 1941 British propaganda movie Pimpernel Smith, a re-working of the Scarlet Pimpernel story, in which an eccentric Cambridge professor helps German intellectuals interned by the Nazis to escape. “That’s the kind of thing I would like to do,” Wallenberg is reported to have remarked.

Whatever the reasons, Wallenberg, a young man of 32, found himself on his way to Hungary. After the Nazis assumed forcible control of the Hungarian government in October 1944, he energetically ran an enormous operation which gave “protected” status—Swedish diplomatic immunity—to houses in the “International Ghetto” (Budapest’s District XIII), issued official-looking but generally bogus papers to Jews with (increasingly flimsy) connections to Sweden, ran soup kitchens and gave medical support, all backed up with fearless personal interventions with Nazis and local authorities. Estimates of the number of lives saved vary, but tens of thousands of Budapest Jews probably owed their survival to Wallenberg’s efforts.

An intriguing side-question often arises: was Wallenberg himself Jewish? Herschel Johnson, US Ambassador (“Minister”) to Sweden during WWII, described Wallenberg as “half Jewish, incidentally”. This was an overstatement, although he was, this biography tells us, one sixteenth Jewish on his mother’s side, via her paternal grandfather, an 18th-century immigrant to Sweden. Wallenberg’s business experience in Haifa and his work with Kálmán Lauer, himself a Hungarian Jew, may well have sharpened his sympathy for the plight of Budapest’s Jews.

The second half of the book is taken up with the story of Wallenberg’s disappearance into the Soviet Union’s prison and gulag system. As the Soviets advanced across Budapest in early 1945, Wallenberg crossed Red Army lines willingly with a briefcase full of plans for Hungary’s post-war reconstruction. He was never seen in the free world again. Concrete or credible news of what happened to him was never provided, though he was clearly in Moscow’s labyrinthine Lubyanka prison immediately after the War. Uncorroborated sightings and reports emanated for decades after, cruelly raising hopes in the hearts of his ever-loyal half-siblings and their children, but he may have been murdered as early as 1947.

Clearly judging on results, Wallenberg was a hero, a man whose personal actions, under instructions from no higher authority than his own conscience, saved thousands of lives. But questions were raised as to his methods: corners were cut; large sums were disbursed with minimal cash accounting; there were significant “related party” provisions deals where his Mid-European Trading Company was the counter-party; involvement in black marketeering was hinted at. But in fact there was no suggestion that Wallenberg personally profited in any way. Knowing how things worked, he had been clear when he spoke to Stockholm’s chief rabbi that the success of his Budapest mission would depend on bribes, and surely some of the plentiful resources of food and money at his disposal were deployed to buy the support of enemy individuals. While the flimsy pieces of paper implying a Swedish connection may have had some effect in occasionally taming the bloodthirsty urges of the German Nazi and Hungarian Arrow Cross thugs, Wallenberg’s connections, oiled by bribery, to their superiors—possibly all the way up to the crazed and drunken Eichmann—were no doubt at least as effective.

The Communists were uneasy with the Wallenberg legacy. The institutionally dishonest world of Hungary’s post-war Stalinist regime needed morally clear and unambiguous tales of herosim. The liberation of Budapest’s ghettos by Soviet troops was one instance where they could genuinely show themselves to have been on the right side. Wallenberg, however, was problematic as a socialist hero: he had aided Budapest Jewry and saved thousands of lives but he had a capitalist family name, had been in the pay of the Americans, had engaged with the “enemy” and—embarrassingly—had disappeared in Stalin’s Russia.

The USSR’s problem with Wallenberg was the USA’s propaganda boon. Wallenberg’s unimpeachable goodness stood in stark contrast to his probable murder—either executed or tortured to death—at the hands of the KGB. For four decades the Soviets proved unable to give a straight answer as to what had happened to him. This was a gift for the CIA, who throughout the Cold War were urgently seeking ways to undermine Soviet credibility with its supporters in the West. And indeed the USA pressed its advantage by making Wallenberg an honorary US citizen in 1981 (the first after Winston Churchill), to give them an official channel for attacks on the Soviets to release information as to Wallenberg’s whereabouts or fate. What is also well catalogued in this book is Sweden’s official pusillanimity. At the beginning of the War, when Germany seemed to be winning, neutral Sweden adopted a policy of accommodation with her powerful neighbour across the Baltic. Later, and also during the Cold War, it was the USSR whom she sought not to offend—certainly not by championing a maverick aristocrat who had gone rogue behind enemy lines and had always had an uneasy relationship with official channels.

This book is a crisp and sympathetic biography, a brilliant and clearly-told history (particularly interesting on Sweden during and after WWII), and an excellent addition to the canon on the Holocaust. Recommended reading.