For many years in the buildings adjoining the magnificent church of Santa Croce (in the rooms around the sacristy and in the great refectory) some important works of art have been on a temporary display. A few weeks ago a definitive arrangement of them was presented to the public. They have been housed in the conventual buildings since the first years of the 20th century (when they were rescued from religious houses suppressed by Napoleon).

In the last few decades Santa Croce has found itself in a rather unhappy geographical position: on a straight street which provides an entrance to the city from the ring-road, which makes it a favourite place for bus tours. An added attraction is the old-established ‘leather factory’ attached to the church, and leather goods are now sold in the shops on the approach so that, all in all, it represents a perfect stopping place for tour groups which are being hurried on their way from Venice to Rome, but in this way can also fit in a few hours in Florence en route. So it is all the more important that if you are on your own and the church becomes too crowded (as it more often than not does by mid-morning), you can now visit the quieter areas which have been beautifully restored.

Close to the famous frescoes by Giotto in two chapels at the east end of the huge church, you enter a corridor off which is the sacristy,where Cimabue’s famous painted Crucifix has at last found a permanent position. It was the most important work of art in Florence to be damaged in the Arno flood of 1966. After a spectacular restoration it is now hung high enough in this beautiful room to be safe from the waters of the Arno should they ever break their banks again. Painted before 1288, it shows Christ ‘patiens’ (suffering) rather than ‘triumphans’ and is for that reason a particularly dramatic figure. The sacristy, because it was part of such an important religious house, is very spacious and has its own ‘chapel’ covered with splendid frescoes by Giovanni da Milano, one of the most interesting followers of Giotto.

From the sacristy you can now go into an adjacent room which has a well in a niche frescoed by Paolo Schiavo, currently being restored. The well would have provided fresh water for the lavabo that was once here. The walls have now been hung with panel paintings (from suppressed churches and convents) which have been in storage here ever since the first years of the 19th century. A triptych by Giovanni del Biondo is dedicated to St John Gualberto, with stories from his life. A modern frame has been reconstructed around Nardo di Cione’s triptych which is particularly interesting for its predella, which has unusual scenes from the life of Job. Also here is St James the Greater Enthroned by Lorenzo Monaco.

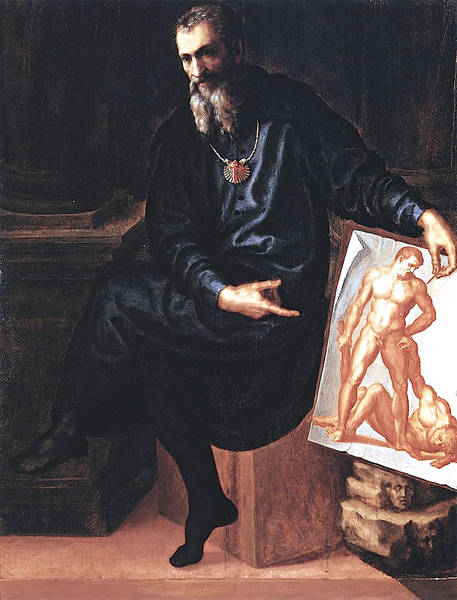

The Chapel of the Novices, built for Cosimo de’ Medici by his favourite architect Michelozzo, is also now open. It houses two huge paintings in wonderful gilded frames by Battista di Marco del Tasso; a Deposition by Salviati and a Descent into Limbo by Bronzino. There is also a Descent from the Cross by Alessandro Allori and a Trinity (with the dead Christ) by Ludovico Cigoli. The enamelled terracotta altarpiece is a della Robbia work and above it a little stained-glass window (designed by Alesso Baldovinetti) has the two Medici patron saints, Cosmas and Damian.

In a tiny barrel-vaulted room off the chapel, with one little window and just large enough to hold a coffin, a bust of Galileo records the fate of the great scientist’s corpse, which was hidden here in 1642 before it was decided he could be given a Christian burial inside the church nearly a century later. In the corridor outside are four gold-ground paintings and a monument to Lorenzo Bartolini, who by the time of his death in 1850 had become the most important sculptor of his day.

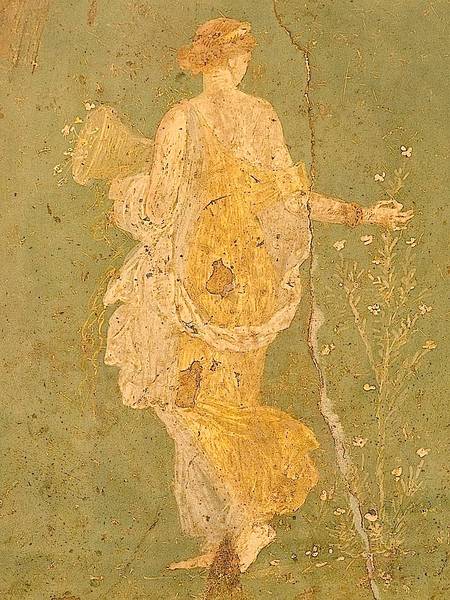

Back in the church itself, beside the very beautiful Annunciation tabernacle by Donatello, a door leads out to the first cloister. At the foot of the steps, behind a white curtain, is the Pazzi Chapel, one of the most perfect Renaissance interiors in Florence. Close by is the second cloister, one of the most peaceful and beautiful spaces in the city. The rooms of the museum here are now a bit shabby, but don’t miss the last room, which has a delightful fragment of the Madonna learning to sew and a fragment of the grieving Madonna in a delicate peach-coloured robe, which found its way here in 1904 from somewhere in the city. In the same room are two newly restored Madonnas, one by the Maestro di San Martino alla Palma, and one by Jacopo di Cione, with the Child in a golden tunic. From this room you enter directly into the splendid Gothic refectory with its huge frescoed representation of the Last Supper by Taddeo Gaddi. This space has now regained its spacious atmosphere. Don’t miss the fresco fragment with one of the earliest views of the Baptistery or the gilded bronze St Louis of Toulouse made by Donatello for the exterior of Orsanmichele.

In a little cloister behind the Pazzi Chapel (entered from the new Information Office) an interesting and well-designed little exhibition illustrates the history of the Arno floods (and a ‘totem’ outside show the various levels the water reached). Also here there is sometimes access to a huge crypt (beneath the sacristy), the ‘Famedio’, a First World War memorial opened by the Fascist regime in 1937 with the names of the 3,672 Florentine soldiers who fell in the fighting inscribed on black marble all around the walls.

As mentioned above, Santa Croce and its piazza can become uncomfortably crowded—but you can slip away from the crowds with the greatest ease if you seek out the little medieval church of San Remigio, in an extremely peaceful corner of town. At the far end of the piazza (the opposite end from the church) take Borgo de’ Greci and then (second left) Via de’ Malagotti, which leads to it directly. The church contains one of the most beautiful 13th-century paintings of the Madonna and Child in Florence, by an unknown master named from this work the ‘Maestro di San Remigio’.

by Alta Macadam, author of Blue Guide Florence, available in print and digital formats.