An exhibition at Palazzo Pitti (Leopoldo de’ Medici, Principe dei Collezionisti, on until 28th January) displays a selection of the exquisite objects from the famous collection of Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici, youngest son of Grand Duke Cosimo II and Maria Magdalena of Austria. Perhaps the most surprising thing about this exhibition is that this is the first time the subject has been tackled, even though it has always been well known how deeply the cardinal’s scholarly taste affected the quality of the Medici collections. The exhibition was conceived by Eike Schmidt, director of the Uffizi and Pitti gallieries, to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Leopoldo’s birth.

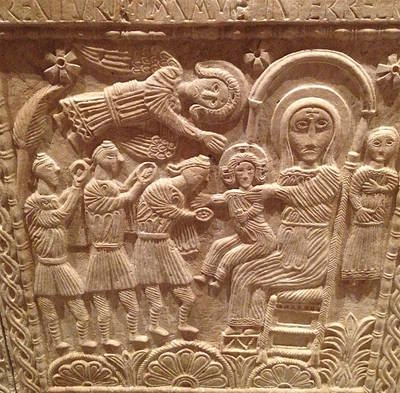

The scope of the artworks on display (in five rooms of the ground-floor state apartments) immediately reveals how widely the cardinal’s interests ranged: antique Roman marble statues and busts, drawings, cameos, paintings, arms, 17th-century ivories, Egyptian statuettes, gems, Etruscan terracottas, astrolabes and all kinds of scientific instruments, small bronzes, Chinese jade, reliquary urns, artefacts in semi-precious stones, Della Robbian enamelled terracottas, artists’ self-portraits, miniatures, still-lifes from the Netherlands, medals and coins, even a tiny Sardinian Nuragic bronze statue. Leopoldo had a wide network of agents who sought out precious art for him (in Rome, for example, he trusted the taste of Bernini and Pietro da Cortona to tell him what he should buy).

The exhibition includes works almost exclusively from the Florentine collections. The cardinal had a memorably ugly face and the visitor is confronted with Giovan Battista Foggini’s marble statue of him, which was commissioned by Cosimo III in memory of his uncle. Other portraits of Leopoldo include him as a baby (tucked up in golden brocade) by Iacopo Ligozzi and the well-known portrait (with no pretence to flattery) from the Uffizi of him as a cardinal, commissioned from Baciccia by his sister Margherita de’ Medici, Duchess of Parma. But the most extraordinary portrait is a large painting by the Medici court artist Sustermans, from the castle of Konopištĕ in the Czech Republic. Leopoldo’s aunt married the King of Poland and she evidently had fun dressing up her nephew in grand style and sitting him upon a grey horse, whose mane flows down over his nose and is draped below his belly reaching all the way to his haunches, where it is tied up by a little red bow. We are told that after the horse’s death its mane was preserved in the Medici armoury. This delightful and amusing portrait (illustrated at the top of this article) was chosen by the curators for the cover of the catalogue.

Another very surprising piece on exhibition is a giant phallus supported by lion’s paws, which was immediately acquired by the cardinal when it was unearthed in Rome beneath the church of Sant’Agnese fuori le Mura (of all places—it is famous now for its early Christian catacombs). It is presumed to have come from a temple of Priapus on the site. Although belonging to Florence’s archaeological museum it is usually kept locked away (it was much enjoyed by the Marquis de Sade in 1738).

Leopoldo’s passionate interest in the sciences is also recorded, with some of the most precious possessions from Florence’s Museo Galileo. We know that when he became titular cardinal in 1667, Leopoldo openly defended Galileo and attempted to clear his name and get his works published. Curios include a transparent green travertine mask from Mexico, complete with its set of teeth, dating from around the 6th century and one of the first Teotihuacan pieces to reach Europe; a lacquer-work and mother-of-pearl box made in Japan in the cardinal’s lifetime and probably where he kept his cardinal’s hat; a 17th-century Indonesian kris (dagger); and a ‘night clock’ which the cardinal had beautifully painted by Borgognone (the copper cover ensured that he was not disturbed in the night by its ticking).

Examples chosen to illustrate Leopoldo’s taste in painting (and his particular interest in the Venetian school), include Titian’s wonderful portrait of the erudite Bishop Ludovico Beccadelli (a touch of white indicating part of his collar gives light to his genial face). The cardinal also owned Veronese’s Holy Family, memorable for the depiction of the Christ Child fast asleep, exhausted by so much attention. The small Portrait Head of a Man was attributed to Leonardo da Vinci in the cardinal’s day but was later recognised as the work of Lorenzo Lotto.

The cardinal is also fondly remembered for starting a collection of artists’ self-portraits. He commissioned some of them from the artists themselves, including Guercino and Pietro da Cortona (others are by Rembrandt, Luca Giordano, Federico Barocci and Ciro Ferri). Tucked away in a corner of the last of the four main rooms is a painting of a musician by Leopoldo himself and three sheets of paper from the Archivio di Stato in Florence with drawings by him illustrating some of his poems.

On the other side of the entrance hall (easy to miss), some of the vast collection of the cardinal’s drawings are displayed. Highlights are a parchment with flowers drawn in black chalk and polychrome pigments by Giovanna Garzoni, one of very few female artists of the time, whom the cardinal promoted and who also painted a miniature portrait of him (on show in the exhibition). This is a splendid exhibition commemorating a great Florentine. The notices and labels (also in English) are excellent.

Before leaving the exhibition it is worth looking into the little Sala della Grotticina where (since the publication of the lastest Blue Guide Florence this year) you can now admire (after its restoration) a wooden trophy exquisitely carved by Grinling Gibbons for Charles II, who sent this by sea to Florence as a gift for Cosimo III. It represents an allegory of the friendship between the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and England (made explicit by a kiss between two turtle doves).

Another exhibition (on until 6th January) at the Biblioteca Marucelliana in tVia Cavour records a collection (much less famous than that of Cardinal Leopoldo) of Italian drawings from the 17th and 18th centuries formed by the Marucelli family. The exhibition is dedicated to the memory of Marco Chiarini, who died in 2015. He was the much admired director of Palazzo Pitti from 1967 to 2000 and also spent many years examining the drawings in the Marucelliana. A catalogue of his studies has come out in conjunction with the exhibition, edited by his collaborators. A selection of the drawings is displayed in the tiny exhibition room at the end of the magnificent Reading Room, first opened to the public in 1752 and still much frequented. The drawings, fascinating for their variety, include fine works by Ottavio Leoni (a portrait of Galileo), Jacques Callot, Sebastiano Conca, Jacopo Vignali, Volterrano and Aureliano Milani. Filippo Napolitano, an artist particularly admired by Chiarini, is also well represented. Chiarini left a drawing from his small but choice collection to each of the institutions he had been most closely associated with in Florence,; he is sadly missed by numerous friends and scholars. Also dedicated to his memory (and to that of his wife Françoise, who predeceased him by a year) is the 11th edition of the Blue Guide Florence, which came out early this year.

by Alta Macadam