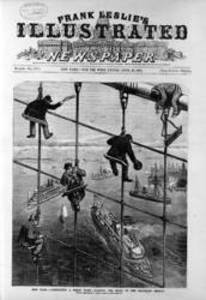

As I write this, it is the anniversary of the birth of one of early America’s great engineers, John A. Roebling (born on June 12th 1806), designer of the Brooklyn Bridge.

When it was opened, in May 1883, Brooklyn Bridge was the longest suspension bridge in the world and an engineering wonder. It is still one of the most majestic sights of New York City.

Roebling had arrived in America in 1831 with a small band of German pilgrims, intending to set up an agricultural community. His talent for engineering soon emerged, however, and he became the country’s most successful producer of wire rope. His design for the bridge that would be built over the East River contained many elements that were new or untested on such a huge scale. His vision became reality, but at the cost of many human lives, including his own. While surveying the building works in 1869 his toes were crushed in an accident and had to be amputated. He contracted tetanus and died. Supervision of the construction passed to his son, Washington Roebling, and his able wife Emily. The foundations of the bridge are sunk deep in the riverbed. In order for men to work them, they had to have air to breathe, and this was solved with a system of caissons, huge diving bells filled with air and submerged in the water. The problems of compression and decompression were not understood in those days and many men suffered from the ‘bends’, including Washington Roebling himself, who was plagued by symptoms of caisson disease for the rest of his life.

Brooklyn Bridge was superseded as the longest suspension bridge in 1903, by the Williamsburg Bridge, also in New York. Today the world’s five longest suspension bridges are in Japan, China (two), Denmark and England. Brooklyn Bridge occupies 78th place. But it is still one of the greatest and most beautiful.

For more on the bridge, and on those who designed and built it, see Carol von Pressentin Wright’s Blue Guide New York.