What is the connection between the Mole Antonelliana, the great 19th-century landmark on the Turin skyline, and Leonardo da Pisa, born at the end of the 12th century and hailed as one of the greatest mathematicians the west has ever known?

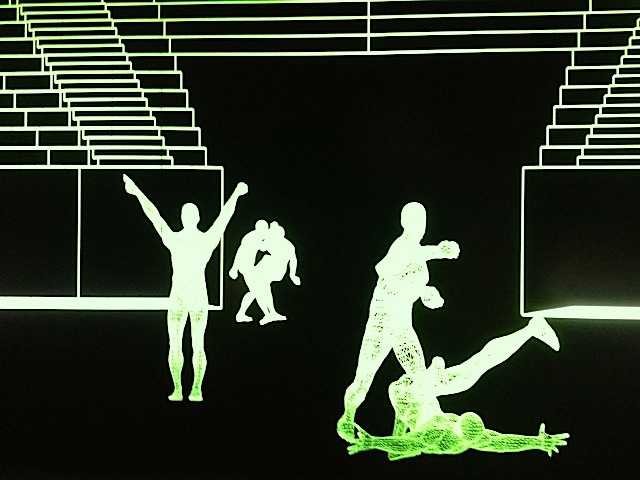

The Mole was begun in 1863 by the architect Alessandro Antonelli. He had been commissioned to build a synagogue by the city’s Jewish community, only a few months after King Vittorio Emanuele had granted freedom of worship to Italian Jews. Antonelli got carried away and instead of the modest structure he had been asked for, he produced something 167m high. The Jewis congregation found an alternative site and the Mole was turned into a monument celebrating the unification of Italy. It is now the Cinema Museum. In 1998 its exterior became host to one variation of Mario Merz’s public light installation known as Flight of Numbers. Merz (1925–2003) was a well-known exponent of the Arte Povera movement. A great part of his oeuvre is dedicated to the numerical sequence known as the Fibonacci sequence, whereby each number is the sum of the previous two. It has been observed to occur very frequently in nature, for instance in the typical number of petals of a flower. The sequence is named after the great north Italian mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci, or Leonardo da Pisa, who set himself the following problem: How many pairs of rabbits will be born in one year, beginning with a single pair, if each pair gives birth to a new pair every month and that new pair begins reproducing from the second month on? The Mole Antonelliana is not the only building to be graced with a Flight of Numbers. There is also one high on a smokestack in Finland, in the city of Turku.

Turin and the Mole Antonelliana are covered in Blue Guide Northern Italy and Blue Guide Concise Italy.